1965

ACCVI executive:

Chair – Noel Lax

Secretary – Kathleen Tuckey

Events:

July 23 – A party of Port Alberni scouts (Rolf Bernstein, Ralph Bernstein, Jamie Bracht, Gene Demens, David Roach and Richard Myrfield) climb Marjorie’s Load.

August – Ralph Hutchinson climbs Beauty Peak north of Capilano Lake.

August 16 – “They Hold The Heights They Won” plaque placed on the summit of Victoria Peak by Robert Hagman and 12 inmates from Lakeview Forestry Camp north of Campbell River.

Section members who passed away in 1965: Anne Norrington, Norman Stewart.

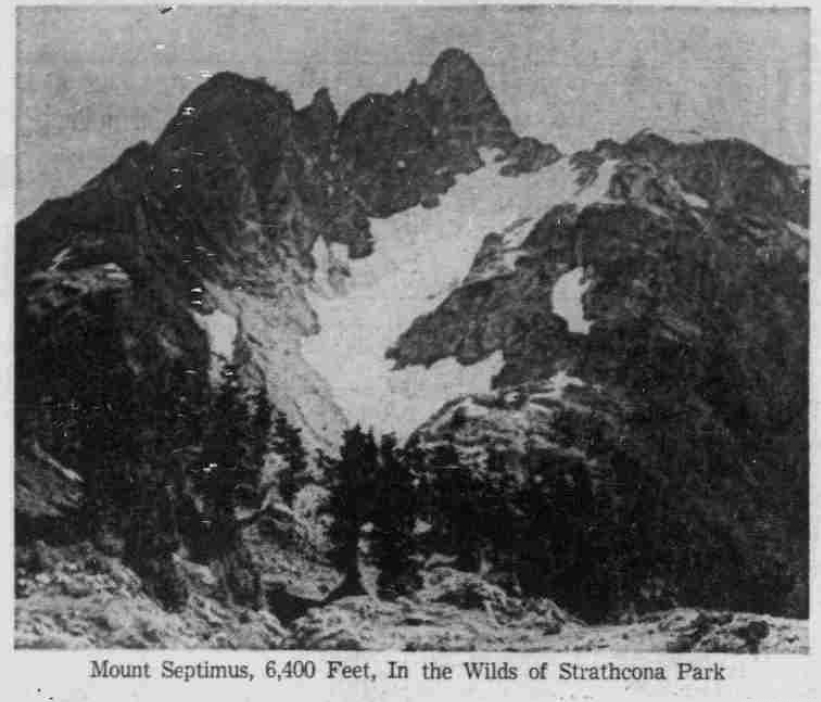

Strathcona Park Story – Richer Than Fort Knox

Reported in The Daily Colonist Thursday February 25, 1965. p.41.

By Jack Fry

Halfway up Vancouver Island lies a string of mountains which may hold enough minerals to make Fort Knox look like a piggybank—mountains which are within the boundaries of Strathcona Park. Since the late 1950’s the mines department has rebuffed attempts at mining in Strathcona Park. The only exception was Western Mines Ltd. which had already established here when the new policy came into effect and which was given permission to mine its gold, copper, silver, lead and zinc minerals near the southwestern end of Buttle Lake. A new problem has now arisen. The mines department has adhered to an agreement made several years ago with the recreation and conservation department that mining will be confined to an 18-sqaure-mile portion of the 787-square-mile park. But indications of rich mineral deposits have been found in other parts of the provincial park, northwest of the present mining area, and pressure apparently mounting for the government to open these to mining interests.

Major Discovery

Some 300 mineral claims are recorded around Myra Creek at the southwestern end of Buttle Lake, including those held by Western Mines Ltd. Buttle Lake Mining Co. Ltd. has about 60 claims and Noranda Exploration Co. Ltd. has holdings there. These were the findings of soil sample and geological surveys conducted by another large B.C. mining company. This company applied for records but was refused because of the mines recreation department’s agreement. To this day, the company which made the discovery has no holdings there. The mines department sent geologists to the new area in 1963. Their findings: “Good indications” that minerals extend in a northwesterly direction into the park from Myra Creek holdings. How large are the mineral deposits there? There could be a King’s ransom in minerals inside the 504,179-acre park but no one is getting to it yet. Applications for records at least 100 claims have been refused in the past several years because of recreation department’s policy of restricting development to some 12,000 acres of Myra creek.

Only One Way In

“There could be another Sullivan Mine (Kimberley, B.C., mineral mine) in there but nobody knows,” said the official. “There had been no extensive exploration because it is a rugged wilderness park with no way of getting in, except the lake.” Ironically, the inaccessibility of Strathcona Park prevented one of the first men who came upon its riches from cashing in his find. Mines officials still remember the day back in the 1920’s when James Cross of Victoria came into their office thinking he has struck it rich. “He was sure he had a mine. He was right, but he didn’t live to enjoy it,” said one official. “He didn’t know how extensive it was but he was a good enough prospector to know there should be some exploration there.” There were the days when the staking of claims and mining in the park were authorized under the Strathcona Park Act, but economics and transportation of the period apparently were major obstacles in Mr. Cross’ path. The Strathcona Park Act was rescinded in March 1957, when the park was brough under the Department of Recreation and Conservation Act.

Negotiations Now

Mining firms which had a toe-hold at the time in the area southwest of Buttle Lake were subsequently allowed to pursue their interests and Western Mines found the riches ores. Western Mines now is negotiating with the recreation and conservation departments with a view to establishing a mining town near its mine inside the park. The company has already been given permission to build a 22-mile road along the east shore of the lake to its mine at Myra Creek. The housing negotiations stirred a new burst of protest from outdoor enthusiasts who say opening of the park to one mining firm will be the thin edge of a wedge which will eventually destroy the wilderness. Whether the present park policy of closure to mining interests will be maintained or whether the government may decide to alter Strathcona Park boundaries to permit more mining has yet to be learned. Until a change is announced the mines department will maintain its present policy. “You cannot get a record for a mineral claim in a Class A park without the approval of the Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation, and their policy to date has been not granting more claims,” a mines official said.

Part Of Key Park Protected

Reported in The Daily Colonist Saturday May 15, 1965. p.5.

By Ian Street – Legislative Reporter

Three large nature conservancies covering about three-fifths of Strathcona Park were established Friday by provincial cabinet order. Recreation Minister William Kiernan said the 302,974 acres involved now are fully protected from all forms of exploitation and “we are serving notice that, as far as we are concerned, these areas are inviolate.” The remaining 227,525 acres in the park revert to Class B parkland status, including the controversial Western Mines Development on the southwest shore of Buttle Lake and what Mr. Kiernan called timber licences, crown-granted mineral claims and recorded mineral claims numbering “in the hundreds.” In Class B parks commercial ventures may be allowed when judged not detrimental to recreational values. Mr. Kiernan said existing alienations in Strathcona will remain and his department will entertain applications for commercial development “on merit.” He said “choice” areas free of alienation make up the nature conservancies. The largest covering most of the western part of the park, includes about 15 miles of the western shore of Buttle lake. It preserves virgin forest, alpine regions and the entire 16-mile length of Moyeha River. This river runs from the glaciated heights of 5,883-foot Mt. Tom Taylor to the head of Clayoquot Sound on the west Island coast. Mr. Kiernan said the Moyeha is the only stream protected throughout its entire length in B.C. and one of the few in this category in North America.

Lakes And Glaciers

In the eastern part of the park, next to Forbidden Plateau, protection was given to an area including The Red Pillar, Memory Lake and several other small lakes and glaciers. In the north, the third conservancy guards Myra and Nola Lakes. A one-mile-wide corridor of Class B parkland was created along the private logging road serving Gold River. A public road to the west planned by the end of this year will also pass through the corridor.

Campsite Planned

Mr. Kiernan said a proposed road to serve Western Mines, running down the eastern shore of Buttle Lake, will also serve a government campsite near Buttle Lake Narrows. Providing this road goes through this year, he said, the government hopes to spend $100,000 in 1966 on construction of the campsite. It will eventually have at least two boat launching ramps and 300 tenting and trailer places.

Circle Route

The campsite could serve as a base for trips to wilderness areas in the nature conservancies. Hiking trails following a circle route are planned in the vicinity of Wolf River and Phillips Creek on the west shore of Buttle Lake. The only other nature conservancy in B.C. is the Black Tusk Meadows region of Garibaldi Park. A fifth is planned at Bowron Lake Park near Barkerville.

Prisoners Home After Saving Injured Guard

Walk For Help After Tumble

Reported in the Victoria Daily Times Thursday August 19, 1965, p. 19.

Thirteen weary prisoners trudged back into jail today after 40 hours of forced freedom. The prisoners, from Lakeview minimum security camp near Campbell River suddenly found themselves alone after their instructor guard fell and injured himself Tuesday. All had left the camp Sunday to climb Victoria Peak, 25 miles west of Campbell River. During the descent their instructor Robert Hagman, 28, of Comox, fell 60 feet onto rocks. Afraid to move in case of internal injuries, the men removed some of their own clothing and built a fire to keep the father of three warm.

Overnight Trek

Then two of them set off through dense forest for an overnight trek to the nearest phone at Sayward. It was well into Wednesday afternoon before they completed the 23-mile march. Meanwhile their companions had down the best they could to make Mr. Hagman comfortable for the night. Wednesday afternoon an RCAF air-sea helicopter guided by instructions from the two men set out to find the party. They located him above the tree-line on the 7,075-foot mountain. The injured guard was whisked to Campbell River hospital where he was in good condition today. He was undergoing surgery at noon for head wounds and a suspected broken wrist. Left without a leader, the prisoners set about making their own way back to camp. On the way they were joined by another party of prisoners led by instructor Joe Kennedy.

Nine Strong

This group, nine strong, had been attempting to climb the mountain from the other side. The climbing expeditions are part of a mountaineering training program aimed at teaching the prisoners leadership and self-reliance. Praising the men’s rescue operation today, camp boss Donald Gray said by radio telephone: “They did a wonderful job. They couldn’t have better demonstrated the value of the course.”

Prisoners Save Guard

Reported in The Daily Colonist Thursday August 19, 1965. p.1 & 2.

Campbell River—Twelve men are walking through 25 miles of dense bush to reach home, after heroic actions in caring for the leader of their mountain-climbing expedition, who was seriously injured in a fall. The 12 men are prison inmates. The man they cared for as he lay unconscious was a prison officer.

Home In Jail

“They’ll come home. They’re almost without food, and they are men serving prison terms for various offenses. They’ve been hiking for five days and they are exhausted. But they will come home.” So said Donald Clay, the officer in charge of Lakeview Forestry Camp, an open prison near here, as he looked with pride on his institution’s rugged mountaineering training program.

Saved Life

That program probably saved the life of 28-year-old correctional officer Robert Hagman, a former Vancouver milkman, who has been working with prisoners only a year. Last Sunday [August 15] morning, Mr. Hagman and 12 inmates started out through the bush, and walked 25 miles through wild country to reach Victoria Peak, west of Campbell River.

Placed Plaque

They began climbing the 7,075-foot mountain early this week, reached the top of the mountain, and placed a commemorative plaque. After a short rest, the men began the descent. “It was tricky and the officer fell,” said Mr. Clay. He fell 80 feet and landed head-on against a rock face. The time was 4:30 Tuesday.

Stripped Clothing

The dozen men climbed as quickly as they could to the spot where the officer lay unconscious. He had severe head injuries, and bruises covered his body. Several prisoners stripped off their clothes and wrapped the officer in them. They supplied what first aid the could. They knew he could not be moved.

Started Fire

Other prisoners rushed down to the timberline, collected wood, carried it back up the cliff, and started a fire to warm Mr. Hagman. Two men, started into the bush at twilight, and walked through the night and the day, with unerring sense of direction, to the nearest telephone at Sayward. At 3 p.m. Wednesday, Mr. Clay was telephoned by one of the men, who gave details of the accident. The prisoner spoke to Air Sea Rescue at Comox, and tried to provide the location in the wilderness. A helicopter took off, followed the directions exactly and touched down several hundred feet from the injured man and prisoners. An Air Sea Rescue official said the accuracy of directions given by the inmate was “almost unbelievable.” When Mr. Hagman was taken aboard the helicopter, air force officials asked the 12 unsupervised men what they planned to do. “Our mission was to come through the bush, climb the mountain, and return through the bush,” a prisoner said. “That’s what we are going to do.” They walked off towards the timberline. Mr. Clay, who was an ardent mountaineer in Kenya a year ago, said he often leads these mountain expeditions himself, and only by chance he did not go on this trip. “This is the essence of our rehabilitation training—self-reliance, responsibility,” said Mr. Clay. The injured man is married, lives in Comox, has three children and another on the way.

Prison Guard Felt Trouble Was Coming Before His Plunge

Reported in the Victoria Daily Times Friday August 20, 1965, p. 17.

By Terry Izzard

Prison guard Robert Hagman had a premonition of disaster shortly before he fell and injured himself. From a hospital bed in Campbell River today, the 28-year-old instructor said: “I had a funny feeling something was wrong. I tried to shake it off but it just wouldn’t go.” On Tuesday the father of three almost lost his life when he slipped and fell almost 200 feet while descending Victoria Peak, a 7,050-foot mountain west of Campbell River. For the next 24 hours he lay in freezing temperatures, delirious, with nothing to eat. “I’d have died of exposure if it hadn’t been for the boys,” said the Comox man. The boys were a group of 11 prisoners from Lakeview minimum security camp who accompanied Hagman on the expedition. Said their instructor: “I couldn’t have asked for anything better. They gave themselves completely. They gave me all the clothing they could and tucked me in close to the fire.” The party had only one blanket. All the expedition members had to keep them warm were their prison coveralls. Two of the youths removed their coveralls to place over Mr. Hagman. “I don’t know how they managed to survive,” said the injured man. “They just froze that’s all.” At first light one of the party, a 21-year-old from Vancouver offered to make the gruelling trek to the nearest telephone – 25 miles away in Sayward. A 19-year-old accompanied him leaving the others at the 5,300-foot level to look after Mr. Hagman, who by this time had become feverish. The Vancouver youth ran most of the way and arrived before his companion. Said Mr. Hagman: “I’ll never know how he did it. We’d had nothing to eat for 36 hours except two small cans of corned beef.” It was Wednesday evening when the youth finally phoned air-sea rescue headquarters. Using the instructions given by the youth, a helicopter managed to pinpoint the injured man first time.

I Was Lucky

He was winched into the copter and rushed to hospital. Thursday he underwent surgery for multiple head injuries and a dislodged finger. Mr. Hagman said: “I was lucky. I slid 150 feet down a crevasse, hit a stone wall, then fell head first for another 20 feet. “I really didn’t know what was happening but the boys apparently lowered me to a safer position. I owe my life to them.”

Convicts Straggle In

Seven Still in Bush

Reported in The Daily Colonist Friday August 20, 1965. p.16.

Three prisoners spent a fifth night in the bush under cloudy skies and showers, on their return trip to camp after their heroic action in caring for the leader of their mountain-climbing expedition who was injured in a fall. Seven other prisoners returned to jail Thursday, weary and unsupervised for 40 hours, amid praise for their part in the action. “The boys were just wonderful,” said Mrs. Robert Hagman, wife of the injured man.

I’m Proud

“I’m proud of those boys,” said Donald Clay, officer in charge of Lakeview Forestry Camp. “This is a good illustration of the success of the training program,” said a spokesman for the attorney-general’s office. The prisoners were part of 12 from Lakeview camp who, accompanied by instructor-guard Robert Hagman, had climbed 7,075-foot Victoria Peak, west of Campbell River.

Rehabilitation

Mountain-climbing is art of the rehabilitation program offered at the camp. On the descent, Mr. Hagman, 28, slipped and fell 60 feet, landing head-on against a rock face. The 12 men climbed down to where the officer lay unconscious, suffering from head injuries, dislocated fingers, and covered with bruises. Five of the men were delegated to remain on the scene while the other seven started the 25-mile hike back to camp.

Walked For Help

Two of the remaining men started into the bush at twilight, and walked through the night and day to the nearest telephone at Sayward. At 5 p.m. Wednesday, Mr. Clay was telephoned by one of the men who gave details of the accident. He telephoned Search and Rescue who sent a helicopter to the injured man following the directions given by the prisoners. Mr. Hagman was flown to Campbell River Hospital, where he is in good condition.

Truck Sent

Mr. Clay Wednesday sent out a truck from the camp to pick up the two men at Sayward. They were back at the camp before the helicopter arrived in Campbell River. Shortage of space in the helicopter forced the other three prisoners who were nursing the injured man to start back to camp afoot, with little food and no sleeping bags. Early Thursday, the seven unsupervised prisoners returning to camp joined up with another group led by instructor Joe Kennedy. This group had attempted to climb the same mountain from the other side.

Final Phase

A spokesman for the attorney-general’s department explained the mountain hike was the final phase of a nine-week training program of athletic and outdoor exercise. During the course, men are taught first aid and survival methods, as well as athletics of various types, including mountain climbing. The program is successful because when the boys go there (Lakeview Camp) they are the toughest and roughest, and in many cases it takes a while in the program before they start to respond,” he said. “These people are against everything, particularly against authority,” he added, “but the program can get them out of their sulky moods by building their self-confidence and self-discipline.

Hikers Tell Story: Guard Fell Giving Aid to Prisoner

Reported in The Daily Colonist Saturday August 21, 1965. p.1 & 2.

By William Thomas

Campbell River—”We were high on Victoria Peak when Mr. Hagman fell,” said Don, a young convict at the Lakeview Forestry Camp, “way beyond the timberline amongst sheets of ice and deep snow.” Robert Hagman, 28, had taken a group of 11 prisoners mountain-climbing, as part of a program to develop their initiative. Jim, just 19, and already an outcast from other B.C. prisons chimed in to say, “We had warned Mr. Hagman not to go near the glacier ice, for two of the other boys had already fallen. It got to be a bit of a joke, us warning him.”

Inmate Slipped

Suddenly it was no joke one of the boys fell on the ice and cut his head as he slithered over into a small gully. Mr. Hagman went to help him and instead he fell, sliding and turning for 30 feet before he dropped over the edge of the ice into a 20-foot ravine.

Man Shocked

I was just stunned and ran across the ice,” said Don. “I knew right away Mr. Hagman was injured.” In an instant the initiative had shifted. Bob Hagman lay streaming blood from head cuts, his wrist useless and his chest aching.

Sudden Drama

The mountain hike had taken on elements of a stark drama. Mr. Hagman was in trouble barely able to move, 7,000 feet up an isolated mountain with little food, no camping equipment and above all dependent on the whim of tough convicts. The events that followed were explained by the two inmates who were instrumental in saving him. We sat in the office of camp director Donald Clay after a massive breakfast of cereal, grapefruit, eggs, sausages, toast, jam and coffee—all prepared by the inmates.

Self Assured

Jim, a lanky, dark-haired youngster with a real sense of assurance, pulled out a map from his hip pocket and gave us the facts. He sounded very much like a military commander outlining a detailed operation. But let him tell it:

Face Down

“I could see Mr. Hagman face down on the ice hard against a rock. By kicking the ice from the overhang I was able to lower my belt to him, and with his good hand he grabbed it. As he came over the lip of the ice he just mumbled ‘I guess I did it this time.’ And he really had.”

Down The Mountain

Don, who was anxious to clear up the details as he saw them, butted in. He was the oldest member of the party—just 21. “I ran down the mountain to where the trees began and with two other boys started tearing up dead branches to get a fire going. It was really tough getting it going.”

No Supplies

By now it was getting dark and all essential supplies were thousands of feet below, at the base of the climb. “Mr. Hagman looked a mess—a bruise over his eye and the blood running down his face made it difficult to realize who he was.”

Made Bandages

It was about now that Mr. Hagman seemed to have gone into shock, explained Jim, who had taken command. “We took off our coveralls and tried to make him as comfortable as possible. By tearing up our undershirts we made bandages and wash cloths to clear up some of the cuts and stop the blood It seemed the longest night most of us had ever spent, just sitting up there on the mountain. The fire helped but when daylight broke by 5:45 a.m. we were ready to put our rescue plan into action. Two of us were to stay with Bob Hagman, three men were sent up the White River to contact another hiking party on the far side of Victoria Peak; another was to hike to base camp and return up the mountain with our blankets and some food while Don and I struck out for a logging operation we knew was in the valley below.” It sounds practical and straightforward but it took hours to complete.

Logging Road

“It was late in the afternoon before Don and I heard the sound of a truck in the distance. We started running through the bush until we hit a logging road. It was just our luck one trucker was a little late in pulling off the job and we yelled to him to stop. It was after 4:30 p.m. and we had been hiking as fast as we could since daybreak. A radiophone in the truck put us in touch with our own camp.”

RCAF Praise

Camp director Clay called rescue officials at RCAF Comox and a helicopter was sent to the site. An RCAF officer later told Mr. Clay, “The way your boys pinpointed the location with their map references was just uncanny.” The same evening the boys who got the message out were allowed to visit Mr. Hagman in Campbell River Hospital. Thursday they were awarded a day off to rest up from their ordeal.

Last Come Home

The first words of one of the three inmates to arrive back at the forestry camp after six hard days in the bush were, “How’s Mr. Hagman?” The last three came in at 3 p.m. Friday. They were hungry and tired but prison officials said, “They were in very good spirits.”

Motto Came to Life

“They Hold the Heights They Won”

Reported in The Daily Colonist Saturday August 21, 1965. p.1.

Campbell River—”They hold the heights they won.” This is the inscription on a small brass plate installed in a cairn of looses stones at the peak of 7,075-foot Victoria Peak, in dense bushland north of Campbell River.

Tough Criminals

It sums up the hopes of the entire staff at Lakeview Forestry Camp, an open prison for some of the toughest criminals in B.C. In almost storybook fashion the motto came to life this week, just minutes after the hiking party from the prison installed the plaque, the 11 inmates were called upon to live it up.

Cold Defied

The boys, their average age just 19, came through with flying colors. They defied cold and harsh, dense brush to rescue an injured guard—traditionally no friend of the hardened convict. Don’t be fooled by their tender years. The staff at the camp will concede that the camp has some of the toughest boys that the prison system has produced. For many, the bold experiment at Lakeview is a last resort. Camp director Donald Clay has pioneered the system of initiative development and training in this province, based on the British plan evolved at the Outward Bound School in Wales. Mr. Clay, a former district commissioner in the colonial service in Kenya, is not a professional corrections officer, and neither are the members of his 18-man staff. All have military background, and the essence of the plan is to impart the feeling of spirit de corps that goes with the crack regiment.

Jail Aims High

The training leans heavily on rescue work and proficiency in the bush under tough going. The action of the rescue team this week had the same effect on the Lakeview staff that a major discovery has on a research scientist. Months of training and planning, frustration, opposition, were all drawn to a climax when the accident to Robert Hagman put the whole program to its ultimate test. The boys, who could easily have run away seeking temporary freedom, stayed on the job because of the sense of pride they have developed in Lakeview and its staff.

Had The Guts

B.A. Cave-Brown, an officer at the camp, is a product of one of Britain’s oldest public schools – Winchester. He said, “I hope that as time goes along these young inmates will look back with pride in having had the guts to stick it through the training here. For instructors, it’s not the best paid job in the world, but we all have a sense of purpose and I think the boys here feel this.”

Tough Times Ahead

There will be tough times ahead for the program, but this rescue-for-real will have set a new stamp on the camp and the inmates are already puffing out their chests a little because they are all part of it. Maybe tough military discipline, the wide outdoors, good food and leaders with a sense of dedication will be able to do something where locked doors and iron bars have failed so sadly. Possibly the inmates at Lakeview Camp will set a trend for other camps, where young men will get a chance to prove they too can make a comeback.

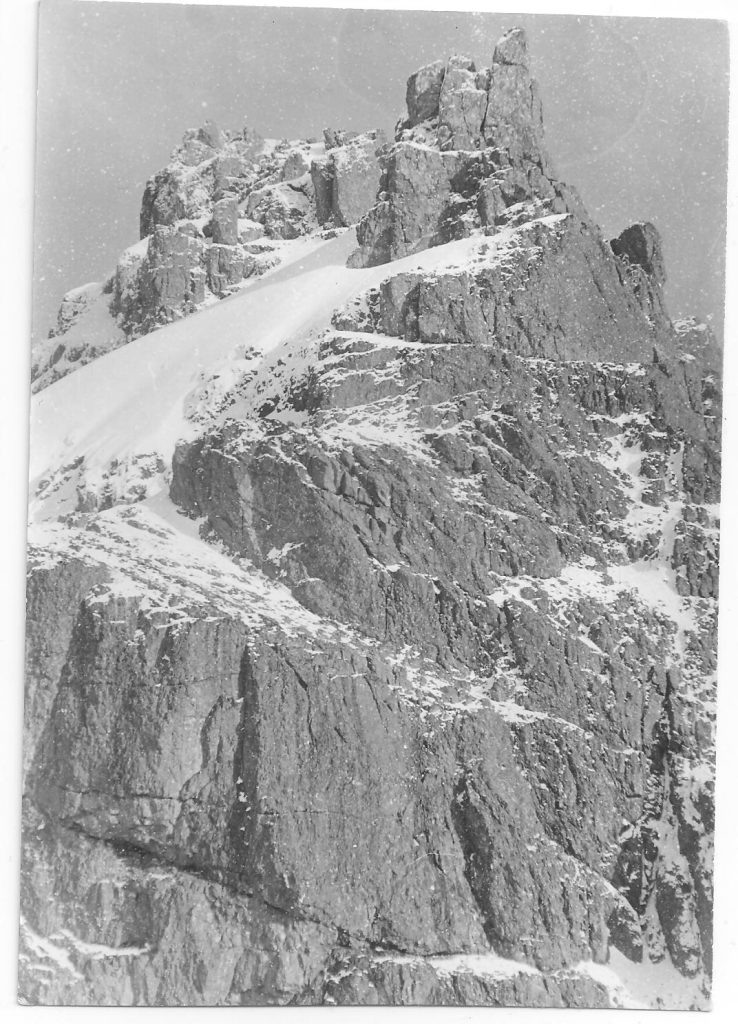

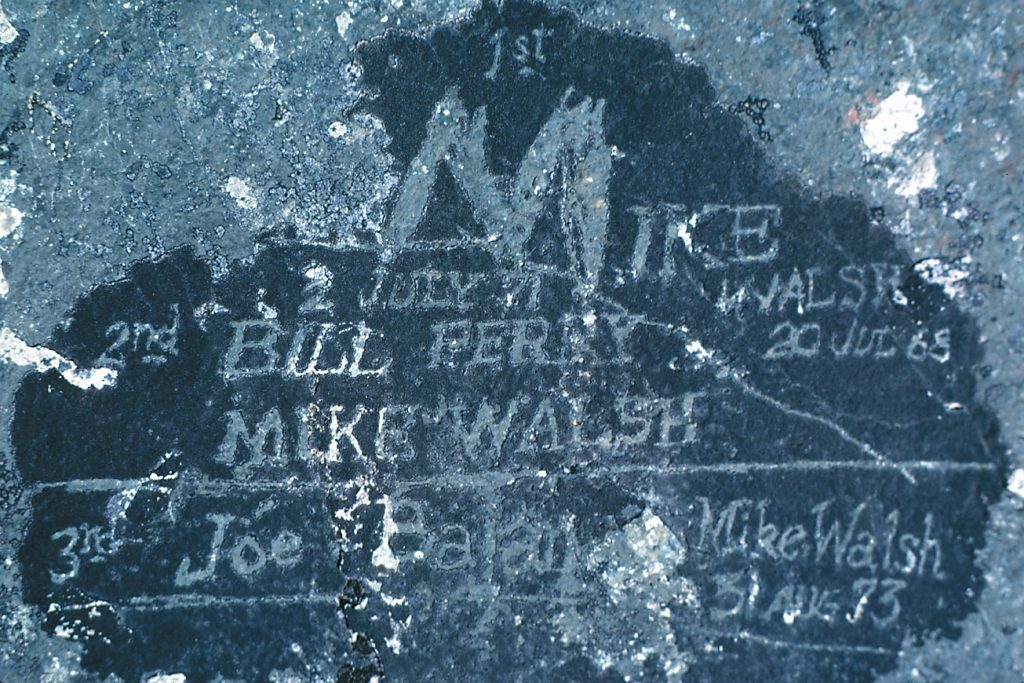

“They Hold The Heights They Won” – Lindsay Elms photo.

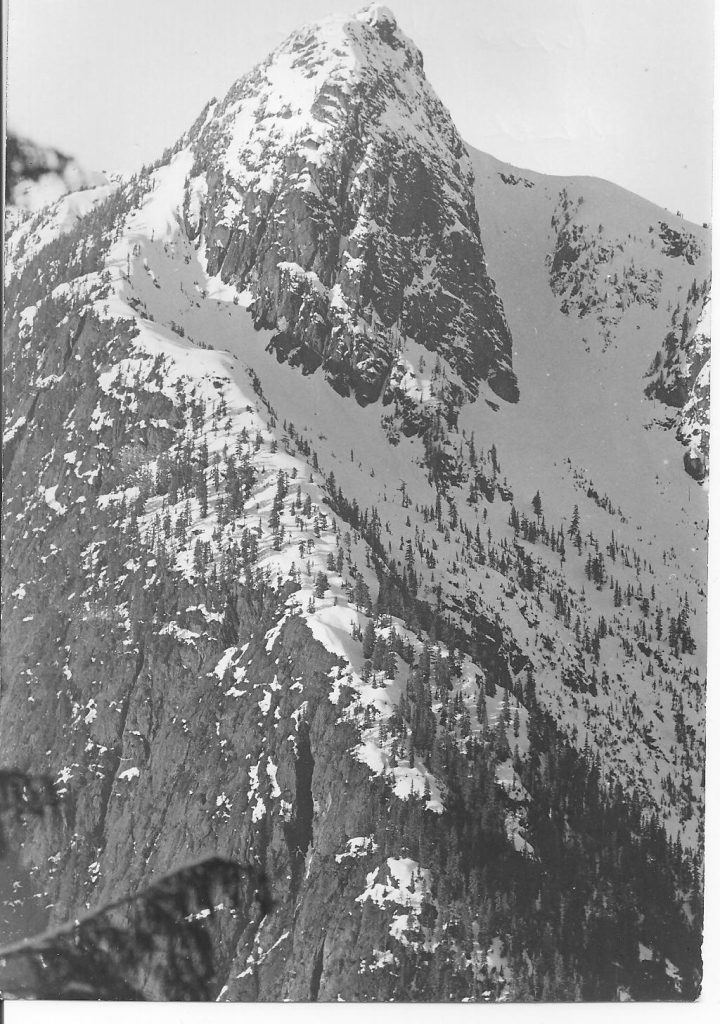

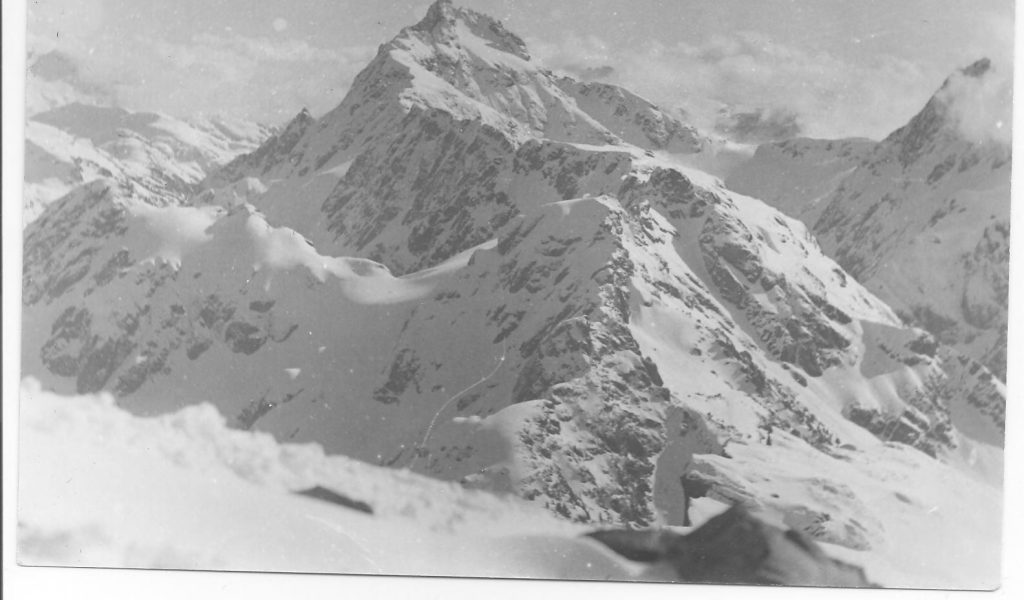

Victoria Peak north face – Hunter Lee photo.

Two Fires Blamed on Hunters

27,000,000 Feet Burned

Reported in The Daily Colonist Thursday September 30, 1965. p.27.

By Alec Merriman

Hunters have been blamed for two fires which destroyed more than 27,000,000 feet of timber in Vancouver Island forest lands in the past few days. The biggest fire was in MacMillan Bloedel and Powell River Company holdings on the east side of Hkusam Mountain in the Kelsey Bay logging division which burned over 1,700 acres. The other fire burned over two acres of crown timberland in the Shaw Creek area back of Cowichan Lake. It appeared as if a hunter came out of the woods wet, lit a fire and didn’t bother to put it out. Fortunately, a timber cruising party in the area chanced upon the fire before it really got going and it was confined to a small area. Even at that fire, fighting costs to the public will be about $2,000. Fire suppression costs of the Kelsey Bay fire will be about $15,000 plus loss of production time. At the peak of the fire 40 men, three tankers and two cats were employed. Monday 15 men, two tankers and one tractor were still fighting the fire and Wednesday patrols were on the spot. The Mac-Powell spokesman said that the fire destroyed113 acres of prime timber, 1,200 acres of marginal timber, and 145 acres of second growth timber. The spokesman said it is not planned to ban recreationalists from the woods because of the fire, but he appealed for more caution in the woods. Evidence points pretty solidly to hunter carelessness. At noon Friday crews were alerted to a fire and when they arrived it was a one-acre fire. But it was in difficult terrain, up a sidehill which acted like a funnel to fan the fire. On the road immediately below the fire were spent shells. Leading to the road from the centre of the fire was a trail of blood. Beside the road were entrails and deer antlers. “It was pretty obvious to us that someone had stood on the road, shot a deer, went up to drag it down to the road to clean it and started the fire by throwing away a cigarette or a match,” the spokesman said. The spokesman said the fire was in a non-operational area where the company doesn’t stop hunters entering on weekdays. The fire was started in an area where there was no one employed, but at least one hunter was known to be in the area and to have bagged a deer. A Pacific Logging Co. spokesman said another hunter left a fire burning in the 19 Creek area around Cowichan Lake, but it was discovered before any damage was done.

Remnants of the 1965 fire near the summit of Hkusam Mountain 2010 – Lindsay Elms photos.

Remnants of the 1965 fire near the summit of Hkusam Mountain 2010 – Lindsay Elms photos.

Dr. Anne Norrington 1876-1965

Reported in the Canadian Alpine Journal Vol. 49, 1966, p.212.

Dr. Anne Norrington, a life member of the A.C.C., who was born at Exeter, Devon, England, in July 1876, died in Victoria, B.C., in her 90th year on October 31, 1965. Dr. Norrington’s early studies were completed in England and after teaching in Exeter she went to Jamaica in 1904, where she taught for four years, then in 1908 she came to Canada to teach at Havergal College, Toronto. In 1917, she obtained her B.Sc. at the University of Manitoba and had an honour of being the first woman to graduate from the University with her degree. Later she obtained her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. She spent many years teaching in the Western Provinces, including five years at the University of Alberta while doing research work, and she also taught for two summer sessions at the Biological Station of the University of Washington. Due to her extensive work in botany, Dr. Norrington was always a keen observer of alpine flora and during her time spent in the Kootenay’s she made a study of the flowers of the Kokanee Glacier, and an illustrated article on these flowers was published in the National Geographic Magazine. It was in 1914 that Dr. Norrington attended her first A.C.C. camp in the Yoho Valley and became a life member. She graduated on Mt. President under the leadership of Ernst Feuz. In all she attended six Club camps and had outings with the Nelson Mountaineers, and in the Cascades with the Washington Mountaineers. During her life Dr. Norrington travelled a great deal and she was always intensely interested in the distinct lines of flowers growing at different levels in the mountains. On retirement Dr. Norrington made her home at her summer cottage in Cresent Bay near Nelson, B.C. and spent her winters in Victoria. Up to her last year she was very interested in the activities of the newly formed Kootenay Section of the Alpine Club of Canada., as she herself had been active in that area in the twenties with the Kootenay Mountaineering Club. She donated her complete set of Canadian Alpine Journals to the KMC in 1964. Our sincere sympathy is extended to Dr. Norrington’s surviving sisters, brothers, and family.

1966

ACCVI executive:

Chairman – Dudley Godfrey

Secretary – Kathleen Tuckey

Events:

April 30-May 1 – Rosseau Chalet work party.

May 21/22/23 – A large party from various club’s attempt Mt. Cobb and Filberg.

June 4/5 – Marble Meadows trail work party.

June 18/19 – A party climbs Klitsa Mtn.

July 9 – Patrick Guilbride, Peter Perfect and Kurt Pfiefer make 1st ascent of Warden Peak.

July – Section member Tom Hall climbs Mt. Logan, Kings Peak and Queens Peak (1st ascent).

July 22/23 – Marble Meadows trail work party.

July 31 – Mike Hanry, Ralph Hutchison, Ron Facer, Bob Tustin, Syd Watts, Mike Walsh, Elizabeth and Patrick Guilbride, Doug Jones, Doreen and John Cowlin, Ray Paine make 2nd ascent of Rambler Peak. Ron Facer and Mike Hanry make 1st ascent of Rambler Junior.

August 1 – Ron Facer, Mike Hanry and Ralph Hutchinson make 2nd ascent of the Southwest Summit of Mt. Colonel Foster.

August 3 – Bob Tustin, Syd Watts, Mike Walsh, Elizabeth and Patrick Guilbride, Doreen and John Cowlin, and Ray Paine make 1st ascent of El Piveto Mtn.

August 4 – Patrick and Elizabeth Guilbride climb Mt. DeVoe.

August 5 – Mike Walsh climbs The Behinde. Takes a fall and sprains an ankle needing helicopter evacuation.

September 3-5 – Syd Watts, Mike Walsh, Ron Facer, Bob Tustin, Doug Jones, Don Apps, Keith Morton, Brian Hooper, John and Doreen Cowlin, and others climb Puzzle Mtn from the Elk River.

October 8/9/10 – Syd Watts leads a trip up Rees Creek.

Joe Bajan, Ron Facer, Bob Tustin and Ralph Hutchinson 1998 – Lindsay Elms photo.

Ron Facer, Mike Walsh, Bob Tustin and Bryan Lee unknown location – Bryan Lee photo.

Section members who passed away in 1966: Ted Greig

Outdoorsmen Oppose Townsite

Reported in The Daily Colonist Thursday March 10, 1966. p.23.

A delegation of Vancouver Island outdoorsmen oppose to location of the Western Mines townsite inside Strathcona Provincial Park will present a brief to a special legislative committee at 9:30 a.m. Friday [March 11]. Sparkplug for the group is Keith Morton of Comox District Mountaineering Club. A caravan will head toward Victoria early Friday morning, picking up along the way delegates from the Courtenay and Campbell River Fish and Game Club, the Island Mountain Ramblers, and Nanaimo, Duncan and Victoria outdoors groups.

Color Slides

During the same hearing, Colonist outdoors editor, Alec Merriman will give the committee a 20-minute showing of color slides taken at Buttle Lake and Strathcona Park. Committee chairman William Speare (SC, Cariboo) said Wednesday the committee would go into an in-camera session after meeting with the outdoors groups and Mr. Merriman, to deliberate recommendations to legislature about the townsite location.

Townsite in Park Would Hit Values

Bad Precedent-Sportsman

Reported in The Daily Colonist Saturday March 12, 1966. p.9.

A precedent for the opening of other provincial parks to commercial developments will be site if Western mines is allowed to have a townsite in Strathcona park, a special legislative committee studying the problem was warned Friday. Keith Morton of Courtenay, who headed a caravan of up-Island outdoorsmen to Victoria, told the committee that a townsite anywhere within the park boundaries would be detrimental to park values. Edward Mankelow of Chemainus, another member of the delegation pointed out that the Western Mines problem is a test case which will greatly influence similar decisions which may have to be made in the future. “It is unlikely that future requests for townsites in parks will be referred to committee. The minister will probably take your findings on this study as the reflection of the views of the public,” said Mankelow.

Public Reflection

Resources Minister Ray Williston told the outdoor group; “We are all emotionally charged in the same direction but we’ve got a practical problem to face up to.” He said the facts cannot be ignored that the mine will go into operation this summer on Myra Creek at the southern end of Buttle lake, and that ore trucks and mine workers will be shuttling back and forth daily along the 25-mile access road into the park.

Notes On Marble Meadow Work Party

June 4/5 & July 22/23, 1966.

Reported in the Timberline Tales of the Island Mountain Ramblers Number 3, January 1967. p.9/10.

In May 1966, permission was secured from Mr. H.G. McWilliams, Director of the Parks Branch to construct a trail from Buttle Lake at the mouth of Phillips Creek to Marble Meadows, elevation 5,000 feet to open up one of the better hiking areas in the park. The letter of permission stipulated that the maximum gradient was not to exceed 15 per cent, cut as little as possible and scatter it well off the trail, and not blaze the trail. During the two work parties approximately one quarter of the trail was taped to the maximum grade, cleared of debris and cut out with a mattock and shovel. In the coming years the trail construction will progress more rapidly in that we will have access to the Western Mines road, thus reducing the time to travel on Buttle Lake. The trail construction will be the major construction of the club [Island Mountain Ramblers] during the next few years.

Rees Creek

October 8/9/10, 1966.

Reported in the Timberline Tales of the Island Mountain Ramblers Number 3, January 1967. p.15/16.

By Syd Watts

Due to the very poor weather forecast the regular Thanksgiving weekend trip was cancelled, and the weather turned out to be perfect. Never again will I cancel a trip due to the weather. So as not to miss a hike during this weekend, a few hikers tried to go up to Memory Lake to see the camping area for the 1967 week’s trip. On meeting at the Comox Lake gate at 8:30 on the Sunday morning, we drove up the Cruikshank main road to the new grade on the left which is just before the Rees Creek crossing. This route soon proved to be of no help as it headed for Capes Lake. Returning to the main road, we drove in on the old Rees Creek grade that leaves the Cruikshank’s main road at the north end of the creek bed. This grade has overgrown and, after driving half a mile, ends in the creek. On leaving the cars we hiked up the old road to the point where it crosses the main creek. We should have crossed over here and stayed on the old grade, but instead, we hiked up on the north sidehill and came on to the grade again on a switchback. A short section of grade is very poor but soon it improves, even though it keeps close to Rees Creek instead of climbing towards the Carey Lakes, as shown on the map. At the crossing of the tributary immediately south of the Carey Lakes, there is a ridge which leads up to the alpine area. This is the route which I had intended to climb – it turned out to be the only route. As the grade looked so good, and as we thought we could climb to the left of the waterfall at the head of Rees valley, we stayed in the valley bottom. Jack Ware and Bill Lash turned back to their car and drove over to the Forbidden Plateau trail to hike to Moat Lake, which Bill had not seen. The rest of the party continued up the grade to its end at the 1900-foot level, which was also the end of the logging operations. Continuing in the timber proved impractical due to the large boulders and the devil’s club. Since the creek bed at this point was dry we followed in the valley bottom, making good time. By now we could see that we were not going to get out of the valley, with walls 1500 to 2000 feet high. It looked like there was a ledge on the north side which would lead us out of the canyon, but after climbing 1000 feet, an open rock fault stopped us from continuing. As it was getting late, we headed back down the valley to get out to the gate before it was closed. This area is worth a trip in to see the canyon. The ridge on the north side of Rees Creek to the Alpine area should have a trail. If the old grade were also opened, one could hike from Buttle Lake at Ralph Creek to the Cruikshank valley. This route would also provide an alternative route to the Comox Glacier and the Forbidden Plateau.

Participants: Syd Watts, Dorothy and Bill Lash, Bill Jackson, Karl Stevenson, Lorne Lanyon, Brian Hooper, Jack Ware.

Rescue Aftermath: Payment For Watch

Reported in The Daily Colonist Saturday July 23, 1966. p.32.

An instructor at a Vancouver Island detention camp, whose wrist watch was lost during an accident last August, will be given $100.53 by the provincial government to make up for the loss. A cabinet order Friday authorized payment of the money to Rober Hagman, a senior instructor at Lakeview Forest Camp. Mr. Hagman was in charge of 11 inmates form the camp. The party had climbed the rugged 7,075 Victoria Peak north of Campbell River and put a plaque on the top. Mr. Hagman went down to help one of the party, slipped and fell 50 feet into a precipice. Two of the inmates walked out of the bush overnight for help. Through excellent pinpointing of the officer’s position on a map an Air Sea Rescue helicopter was able to locate the party next day and carry Mr. Hagman to safety.

Three Climbers Scale Mountain

Reported in the Campbell River Mirror July 1966.

By Mary Baldwin

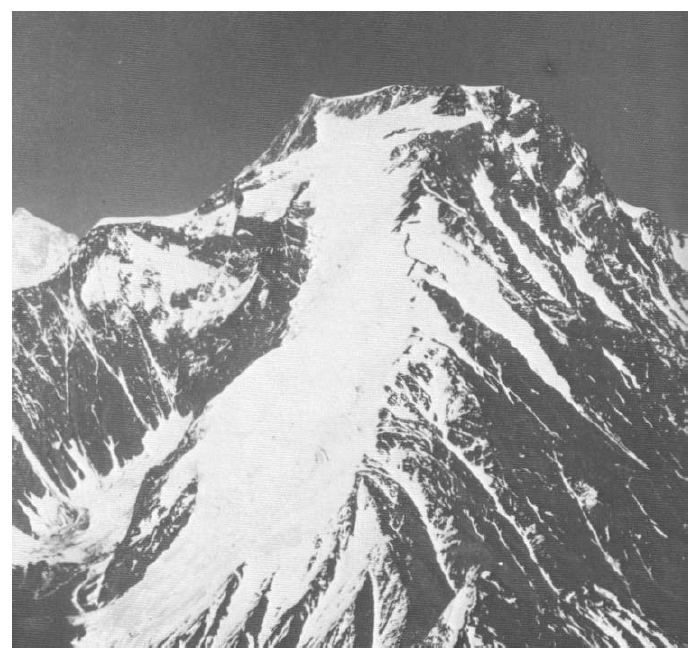

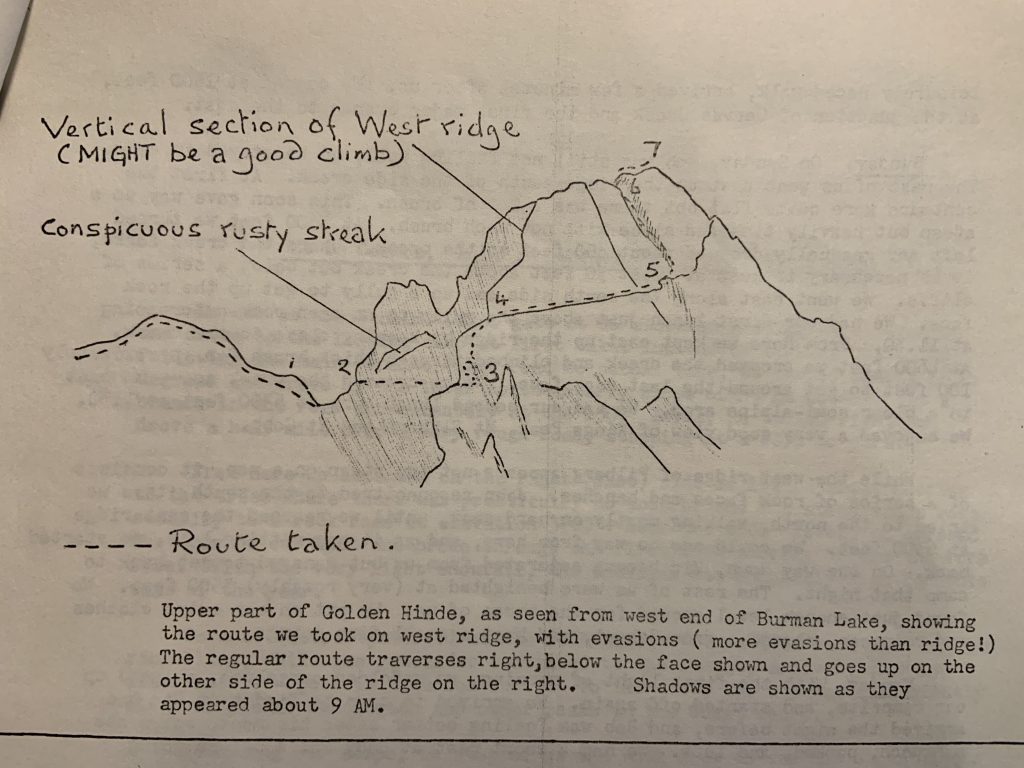

The Thursday’s Province, three Japanese businessmen who had climbed 13 peaks in the Rockies, expressed their surprise that more B.C. people failed to take up the challenge of climbing. These gentlemen have not met a climbing family of Campbell River, the Stapley’s. Frank Stapley is an experienced climber, both of mountain peaks on the island and the mainland. Now his two older boys are following in his footsteps, for they have climbed the Golden Hinde, a mountain in Strathcona Park 7,219 feet high. This is just a beginning. Last weekend, Frank, his two sons Dick and Dougie aged 13 and 12 respectively, together with Mr. and Mrs. Forrest Stotzer of Miracle Beach, left by Island Airlines Beaver plane for Burman Lake, altitude 3,000 feet on the first leg of the journey. This is an isolated lake and has no attraction to the sports-fisherman for there are no fish in this lake. They started climbing on Friday from her, establishing a base camp, but on Saturday morning, they were forced to return to base, for the fog and mist rolled down obliterating the landscape. Frank is no foolhardy climber, he has respect for the climatic conditions, for he has often climbed alone when a false step could be fatal. That was why he decided they must return to base, although they were halfway to their objective. On Sunday the day broke bright and clear, and at 7 a.m. they left for their climb to the peak. They reached the summit at 11 a.m. After a rest and a long survey from this pinnacle, they retraced their steps arriving at the base camp at 3 p.m., all well satisfied with the weekend climb. But at the camp the heavens opened and deluging rain descended on them. It was decided to stay in camp until Monday, in the hope that the weather would clear. Monday did what was expected, and in dry weather the party walked to the Western Mines project at the southern end of Buttle Lake. Here they were treated right royally by mine manager Bruce Laing and the personnel. They were shown over the mine, much to the delight of Dick and Dougie. Then Mrs. Phyllis Stapley was contacted by radio-telephone to be ready to meet the party by car at the Western Mines wharf lower down the lake, for they were being brought there by the mine launch. So the weekend ended happily, but the appetite for climbing has been whetted so that perhaps the Japanese gentlemen who complained mildly about our indifference to climbing will find that there are school children as well as adults who appreciate the thrill of mountaineering.

Outdoors

Reported in The Daily Colonist Wednesday October 19, 1966. p.11.

By Alec Merriman

A new logging road being built by Crown Zellerbach will bring Courtenay’s Forbidden Plateau alpine lake wonderland to within a 15-minute hike for ordinary recreationists who lack stamina of mountain climbers. When plans were announced for a shortcut road through Paradise Meadows to Crown Zellerbach’s operations to the north, in the headwaters of Piggott and Rossiter Creeks, they brought a storm of protests from Island and Vancouver alpine and outdoor groups. They feared the timber bounding Paradise Meadows would be logged and the area would be spoiled. About 200 acres of alpine area was involved. But when we flew into the area on Monday, Crown Zellerbach’s Courtneay division manager Tony Poje assured us the Paradise Creek timber will not be logged “for two or three years. But we have to push a road through there to get access to our timber holdings on the Piggott and Rossiter,” he explained. The hillside overlooking the meadow is wooded, and “we will leave a strip of timber a minimum of 400 feet wide between the road and the meadow.” He also said that when the road is constructed public access will be allowed under normal company access policies, which means during fishing and hunting seasons, except when there is extreme fire hazard. During hot weather responsible organized groups will be able to apply for special permission to use the road to reach Forbidden Plateau access areas.

Satisfied For Now

Comox District Mountaineering Club president Keith Morton told us Tuesday his group is satisfied with the arrangements for the present. It will undertake to place signs pointing the way into the Forbidden Plateau alpine lake area and will mark and improve the old Dove Creek trail, which leads off from Paradise Meadows and used to be the main access route to the area. Morton said the timber corridor plan will give his club and other groups time to try to arrange an exchange of timber so the area may be preserved. Recreation Minister Kiernan told us his parks branch is still interested in the Forbidden Plateau area adjacent to Strathcona Park, and will listen to any proposals the outdoors group may make. But the land in question is E & N land grant property on which all mineral rights, except gold and silver, are held outright. Mr. Kiernan said he is wary of taking over as a park any area with mineral alienations. He didn’t think there would be any chance of negotiating mineral rights except at a fantastic cost and added there have been “interesting mineral discoveries in the Forbidden Plateau area.” Crown Zellerbach brought its Paradise Creek area from the CPR’s E & N land grant properties last year but there remains a corridor of land still owned by the CPR under the grant. It’s the area within Strathcona Park game reserve and adjoining the central-eastern park boundary which contains the lake and alpine areas most used by recreationalists and sought for annexation to the park. Mr. Kiernan said use of the area for recreation purposes will have to be under the multiple use concept.

Within Easy Walk

This alpine lake area is already used by recreationalists who hike in from Forbidden Plateau lodge to the southeast, or use Crown Zellerbach’s branch 62 road to Wolfe Lake and up Brown’s River system—which now end six miles before Paradise Meadows. The new road, to follow the old Dove Creek trail, will be an extension of that branch within easy walking distance of the plateau alpine area. It will be a 22-mile trip from Courtenay. Some of the lakes that will be brought six miles closer to ordinary recreationalists are battleship lake, Lake Helen Mackenzie, Lady Lake, Croteau Lake, Mariwood Lake, Panther Lake and Lake Beautiful. Many have been recently stocked with trout. Moat Lake, biggest of the fabulous chain, may be reached by the Comox Lake-Cruikshank Canyon Zellerbach logging roads which take hikers to within two or three miles of Moat Lake, but expert knowledge is required to get through the network of logging roads. The Comox Glacier may also be reached fairly easily from the Cruikshank Canyon logging roads. The old Dove Creek Trail connects all the lakes.

First Ascent of Warden Peak

Reported in The Canadian Alpine Journal Vol. 50, 1967. p. 55.

By Patrick D. Guilbride

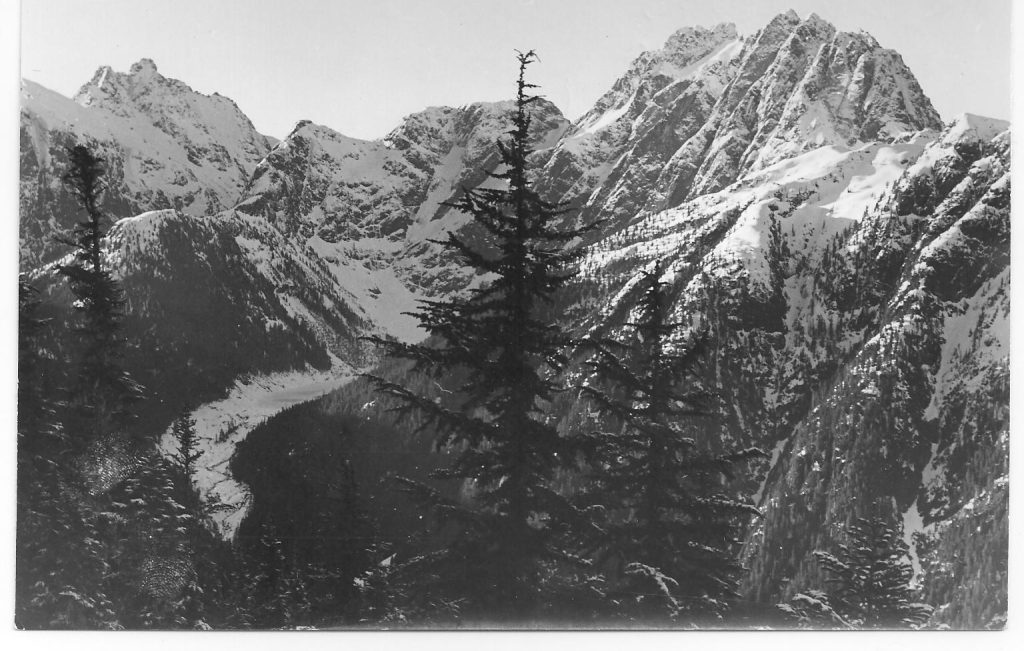

This 6,500-foot rock tower just north of Victoria Peak some 35 miles west of the town of Campbell River remained unclimbed until July 9, 1966, more because of its inaccessibility than its difficulty. This fact was not known to Kurt Pfiefer, Peter Perfect and myself as, after flying into Stewart Lake (about 5 miles east of Victoria Peak) we left our camp at the 4,500-foot level on the southeast slope or Victoria Peak at 7 a.m. in perfect weather. From all sides—from the highway or from Victoria Peak—the summit tower appears to rise unbroken and nearly vertical for 700 feet. The normal route to Victoria Peak was followed to the east spur at 6,000 feet. Here we roped and began a traverse across the east face of Victoria to the glacier in the Warden-Victoria Col. The next quarter mile took nearly 4 hours of step kicking. The route is nearly level, on a 40-degree snow ledge, with a sheer drop of never less than 500 feet always just on your right. The face above sends down rocks to relieve the monotony of step-kicking in the hard snow. We moved one at a time, always keeping two axe belays on the rope. The col was reached at 1 p.m. after a roped glissade down the glacier. Scree and more steep snow brought us under a gully leading to the west ridge of Warden about 300 feet below the summit. Some scrambling up very good rock on the north face resulted in our reaching the summit at 4 p.m., where a cairn was built and names deposited. Thinking that we would surely be benighted somewhere on the traverse, we did not linger. Thanks to our steps of the morning, now frozen and secure, plus a few short-cuts on rock rather than snow, we made it back to camp before darkness. Supper was being eaten and tea consumed until midnight. Drizzle next morning, but sunshine by the time we reached Stewart Lake, and we had the afternoon to spent fishing (fruitless), swimming, and sun-bathing. The Alert Bay Airlines floatplane finally arrived at 8 p.m. The shortness of the lake and possibility of down-draughts necessitated very careful checking of the weight-load for take-off.

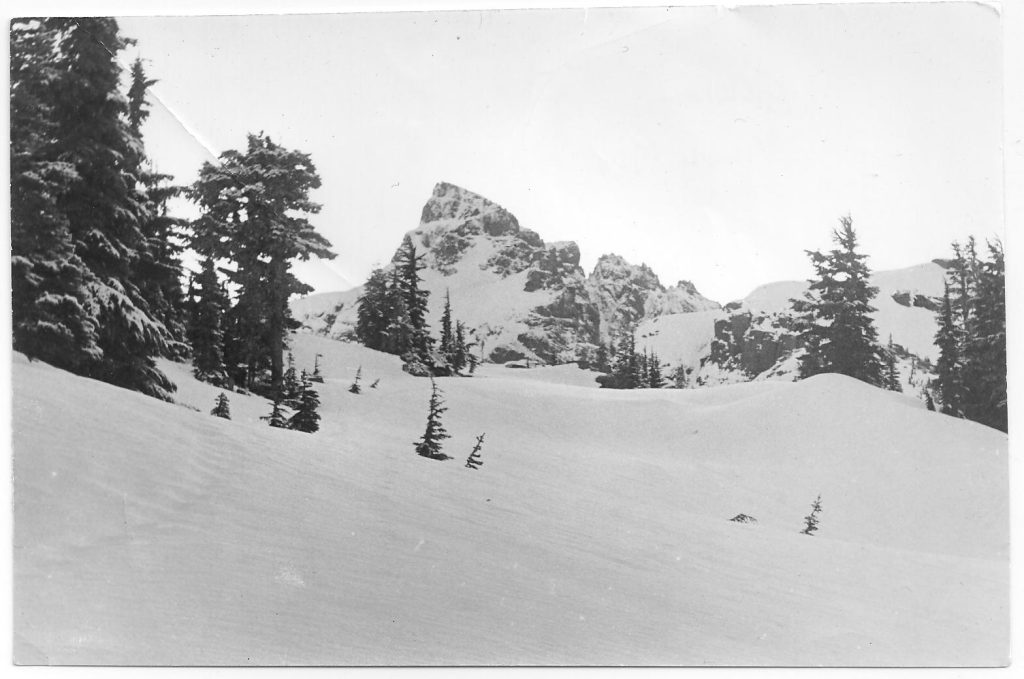

Warden Peak 2006 – Lindsay Elms photo

Second Ascent of Mount Colonel Foster

Reported in The Canadian Alpine Journal Vol. 50, 1967. p. 55/56.

By Ralph Hutchinson

The first ascent of the South [Southwest] Peak of Mt. Colonel Foster in Strathcona Park, Vancouver Island, was made in 1957 by a party that climbed a couloir up the west face. On joining the summit ridge, which runs north and south, they said a route looked feasible from the south if the descend could be made from the subsidiary summit to the south. On August 1, 1966, six climbers from the Island Mountain Ramblers’ camp on the ridge that divides the watershed of the Elk River and the Wolf River, set off to traverse the subsidiary summit to the south (known in this article as the East Peak) and climb the ridge route to the main South Peak. By 11:15 a.m. all members of the party were on the summit of the East Peak after an interesting and pleasant grade 3 rock climb. The weather was beautiful and for half an hour the party considered the route off to the north which looked both exposed and difficult. The ridge to the South Peak from the East Peak is obvious in that there is only one practical route. After rappelling 25 feet to an insecure stance, three of the party, Ron Facer, Mike Hanry, and I proceeded gingerly along the knife-edge ridge. This is spectacularly exposed and dips to a notch where a gully joins the ridge before rising up to the South Summit. The rock was firm and provided good holds and good grade 4 climbing. At the point where the ridge ended, there were alternative routes; one was northerly up the rock face which was probed by Ron Facer. The alternative route led down to the west in the gully for 200 feet, and then by a traverse to the north joined a branch of the same gully. This latter route was chosen and led up, first under a colossal chock stone and then onto a point on the ridge to the south of the summit. From there an easy scramble took us onto the pinnacle that forms the summit tower. It was now 2 p.m. and we dug into the cairn and found the 1957 record in excellent condition. Our ambition had not been sated and as the centre peak on the ridge is almost as high as the South Peak, we investigated the route along the ridge off to the north. We were now some distance from the campsite and did not have any bivouac equipment so we felt no more than mild curiosity to see if the ridge would go; on finding difficult climbing ahead, we retraced our steps and rejoined our friends Mike Walsh, Ray Paine and Bob Tustin. Mount Colonel Foster has a remarkably dramatic east face. This forms an arc around a lake at 3000 feet and the face rises to the summit ridge at 7000 feet in an uninterrupted sweep. There are several small couloirs up the face and towards its southerly side are two snowfields perched somewhat precariously on the rock. The three of us who had been to the South Summit decided to make a bid for the centre peak by traversing between the two snowfields. If that could be achieved, then the ridge could be gained from the top of the upper snowfield without too much difficulty, and lead to the base of the centre peak. The Bitterlich [Ulf and Adolf] brothers had tried this route in 1955 although we did not know this at the time. We were able to gain the top of the first snowfield without untoward difficulty although the climbing was interesting and exposed. From there we made several false leads in our endeavours to get over to the second snowfield. Some hours later the attempt was abandoned after some extremely difficult leads had been made by Ron Facer. At this point it is most difficult to see the route as parts of the mountain overhang and the mountain is very broken up partly as a result of the strata and partly as a result of a large earthquake about 20 years ago. The earthquake had its advantages as there is very little loose rock on the east face of the mountain. The route chosen across the east face is feasible and when mastered will provide a varied and excellent ascent to the unclimbed centre peak.

The sweeping East Face of Mt. Colonel Foster taken while flying in to Elk Pass July 30, 1966 – Ralph Hutchinson photo.

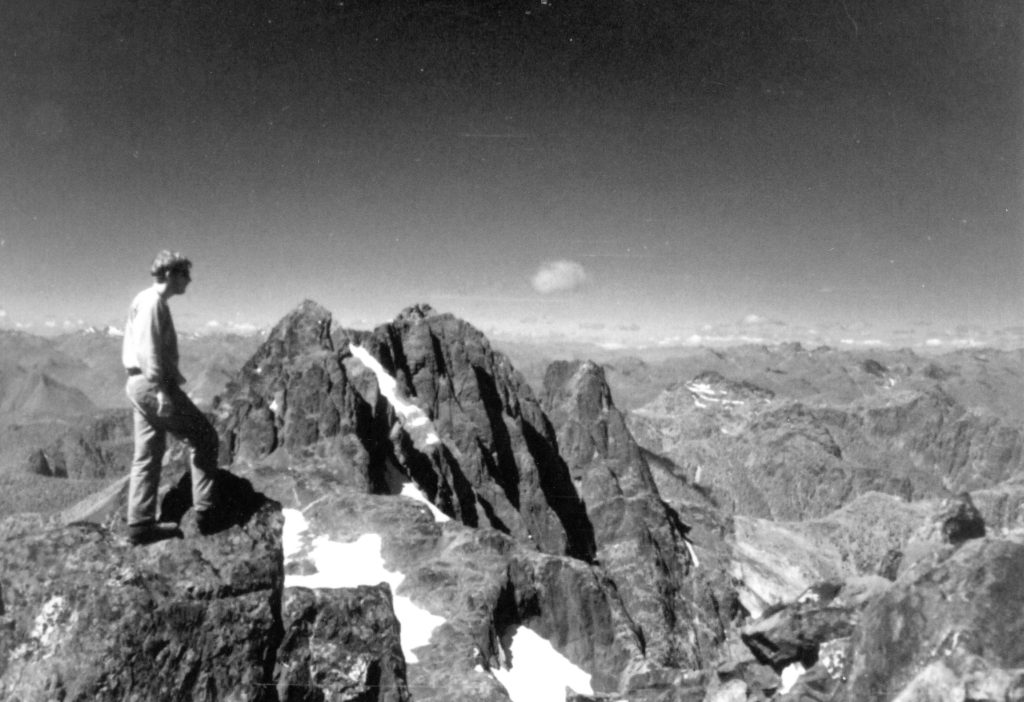

On the Southeast Summit of Mt. Colonel Foster looking towards the Southwest Summit, August 1, 1966 – Ralph Hutchinson photo.

Climber (possibly Ron Facer) ascending the west gully up to the ridge on the Southwest Summit of Mt. Colonel Foster, August 1, 1966 – Ralph Hutchinson photo.

Climber (possibly Ron Facer) ascending the west gully up to the ridge on the Southwest Summit of Mt. Colonel Foster, August 1, 1966 – Ralph Hutchinson photo.

Climber (possibly Ron Facer) on the final ridge to the Southwest Summit of Mt. Colonel Foster, August 1, 1966 – Ralph Hutchinson photo.

Week on Elk-Ucona Pass

July 30 to August 6, 1966.

Reported in the Timberline Tales of the Island Mountain Ramblers Number 3, January 1967. p.10/11/12/13.

By John Cowlin and Elizabeth Guilbride

July 30 – A party of 11 met the Okanagan helicopter at the burrow pit beside the junction of the Gold River and Cervus Creek. At 20 minutes per return flight we soon travelled in pairs, effortlessly but expensively, up the Cervus Valley, between Elkhorn South and Rambler North to the snow-covered pass. A greeting party consisting of Ray Paine and Dave Birch who had hiked in from Buttle Lake, and Mike Walsh and Doug Jones [hiked in the Elk River] were glad to see us. After setting up our tents at various locations where we would find a snow-free clearing near the pass, we meet by a campfire and planned to climb Rambler Peak the following day.

July 31 – Rambler Peak, Ron Facer leader (second ascent). A party of 12 left the pass at 8:30, ascended the south saddle to elevation 5,700’ and scrambled to the snowfield [via Spiral Gully] to the east side of the main peak of Rambler, where we divided into two groups. Mike Hanry and Ray Paine climbed the East face of the main peak, while the rest of the party scrambled up a chimney on the north-east slope, reaching the summit soon. After lunch Ron Facer and Mike Hanry made a first ascent of the south peak [Rambler Junior] of Rambler by a traverse along the east face and back up the southerly skyline ridge to the summit. The rest of the party watched and dozed on a nearby knoll in the warm afternoon sun.

August 1 – Mt. Colonel Foster 7,000’. In 1957 the first ascent of the South Peak [Southwest Summit] of Mount Colonel Foster was made by Ferris Neave, Hugh Neave and Karl Ricker. This was reached by climbing the couloir that led up the west face, and the party had previously bushwhacked up Butterwort Creek to gain the gully. (The Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 49, 1957. p.35). On August 1, a party consisting of Mike Walsh, Ray Paine, Bob Tustin, Mike Hanry, Ron Facer and Ralph Hutchinson, set off intent on climbing the subsidiary summit to the south, known in this article as the East Peak [Southeast Summit]. That peak had been climbed first in 1954 by Syd Watts, Pat Guilbride, Bill Lash and Mallory Lash, [in fact the first ascent was in 1936 by Alfred Slocomb and Jack Horbury] and we hoped to negotiate the intervening ridge. By 9:30 we were on the col to the south of the mountain and by 11:15 had reached the East Peak. The weather was glorious and this fine mountain invited some further investigation, so we reconnoitered the ridge leading to the north, and after a great deal of hesitation, three of the party took the plunge and rappelled onto the knife-edge ridge that dipped down before rising up to the South Summit. This ridge was spectacularly exposed and in places appeared to overhang the East Face, but the rock was firm and had good holds. At a point where the ridge ended there were alternative routes: one was northerly up a rock face which was probed by Ron Facer. The alternative was down the gully to the west for 200’ and then traversing to the north to join a branch of the same gully. This latter route was chosen and led up, first under a huge chock stone, and then on to a point on the ridge south of the summit. From there an easy scramble took us onto the pinnacle that forms the summit and we found the 1957 record in remarkably good condition. It was now 2 p.m., so we investigated the route off to the north, but found no practical way of carrying on the ridge. After spending some minutes in that area we retraced our steps. As none of us had mastered the art of rappelling uphill we were concerned about the last few feet up to the East Peak. When we returned there we found a fine crack, which in conjunction with a right angle in the rock formation that gave plenty of purchase for the back, enable us to rejoin our friends without their assistance. On the South Summit had been Ron Facer, Mike Hanry and Ralph Hutchinson.

August 2 – Restful day. After two energetic climbs and still good weather, the party took a day of rest. The Guilbride’s [Pat and Elizabeth] hiked around the lake immediately south of the pass, the boys hiked to the lake just south of Colonel Foster, while Syd Watts, Doreen and John Cowlin hiked onto the ridge southwest of the campsite. Ralph Hutchinson and Ray Paine remained at camp to relax and catch up with domestic chores. During the morning Doug Jones, Gregg Shoop and Gregg’s lass from London reluctantly left the party and took a slow twelve hours hike down the Elk Valley to the Gold River Road and civilization.

August 3 – El Piveto Mountain 6,400’ Leader Pat Guilbride (First Ascent). A party of five left the pass at 7:30, climbed the south spur of Rambler Peak and dropped down to a lake at elevation 4,400’. Ray Paine, Mike Walsh and Bob Tustin followed, but the latter two left their packs at the lake as they had planned to hike to the Forbidden Plateau to join the second week group. From the lake the two parties climbed the westerly slope to the northerly ridge of an unnamed 5,600’ bump [Cervus Mountain] upon which a cairn was erected. Descending the easterly slope, we crossed a snow saddle and started up El Piveto Mountain. From the pass we veered south-easterly to scramble up the southerly rock to the snow slopes which led to the summit. Near the summit this mountain is a mass of conglomerate cemented together with reddish rock. Mike Walsh had beat us to the top and erected a cairn, after which w saw Bob and ray climbing the lower northerly peak and joined them. Just before Bob and Ray reached the summit ridge, a large rock dislodged, gashing Ray’s leg and bruising Bob’s chest. While Bob escaped with bruises, Ray had to be bandaged with his undershirt, the only available bandage. From the summit of El Piveto we enjoyed a magnificent view of the Golden Hinde, McBride, Cobb, Con Reid and Rambler, to name some of the higher peaks. We also saw the south fork of the Wolf River and even part of Buttle Lake. Ray, Mike and Bob descended slowly by the same route to the lake where Mike and Bob picked up their packs and hiked southerly to a round lake at elevation 3,800’ where they camped. The rest of the party retraced their steps to camp, taking about twelve hours for the return trip. Those making the first ascent were Mike Walsh, Bob Tustin, Ray Paine, Pat and Elizabeth Guilbride, Syd Watts, Doreen and John Cowlin. At the same time Ralph Hutchinson, Ron Facer and Mike Hanry climbed the northerly ridge of Rambler Peak to look across and find a possible route up the North Peak of Colonel Foster.

August 4 – Three days later Mike Hanry, Ron Facer and Ralph Hutchinson revisited Colonel Foster with the view to forcing a route across the East Face to the Centre Peak. There are two snowfields on the East Face and, if a party could negotiate the traverse from the southerly snowfield to the upper snowfield, the route should be both varied and fast. This opinion had been reached after considering the ridge route from the south. It appears the Bitterlich Brothers [Ulf and Adolf] tried the East face in 1955, but were unsuccessful, though we did not know this at the time. Unfortunately, we were no more successful, and several false leads used up valuable time and energy. After some hours the attempt was abandoned, but not before some impressive climbing on the part of Ron Facer, amply protected by safety pitons and well encouraged by the abuse of his belayers who preferred larger holds and less exposure. The climbing on the East Face is excellent as the rock is firm, the exposure is dramatic (the face sweeps down 4,000’ to the lake and is well guarded) but the holds are minimal and smooth. When this route is mastered, it will provide a fine climb to the centre peak.

Mt. DeVoe. The Thursday, another fine day, saw varied hikes, depending upon the desire of the participants. Pat and Elizabeth Guilbride hiked southerly to Mt. DeVoe by way of the ridge south of the pass, the west shore of the circular lake and connecting ridge to the summit. Syd Watts, Doreen and I [John Cowlin] set out to see if any Douglasia was growing on the southerly face of Rambler Peak. This pretty pink flower which was thought to be native only to the Olympics, has been found on the higher peaks in Strathcona Park, above the level of the last ice age. We found a bright clump well above the level of vegetation, and completely surrounded by bare rock.

August 5 – As this was the last day before the helicopter was due to come and pick us up, we decided not to go far from camp in case it came in early to leave a message. So five of us hiked up on the south spur of Rambler Peak and spent an easy day taking photos, looking for wild flowers, and eating a very leisurely lunch. The party consisted of Syd Watts, Doreen and John Cowlin, and Pat and Elizabeth Guilbride.

August 6 – When the helicopter arrived at 10 a.m. we were already to load the equipment just as soon as it landed. At $140 per your rental, no minutes can be wasted. Shortly after 11 o’clock the seven of us were out in four trips. Mike Walsh and Ron face had walked out the previous day. The weather, the challenge of the mountains, the flowers, and most important, the company made this a memorable week’s holiday.

Postscript

By Lindsay Elms

After climbing The Behinde, Mike Walsh fell and sprain his ankle and needed helicopter evacuation. Bob Tustin rushed out to Buttle Lake and got help for his injured mate. Many of the others from the previous trip—Syd Watts, Doreen and John Cowlin, Doug Jones—returned to Forbidden Plateau for a second week of hiking and climbing with other members. Bob Tustin [and Don Apps who joined this part of the trip] eventually caught up with the party on Monday night at Circlet Lake. Doreen Cowlin takes up the story.

August 9 – Late last night I awoke to hear two unknown visitors come into our camp, and wondered just who wandered around this area in the middle of the night. My curiosity hurried me out of the tent in the morning and I discovered that the late arrivals were Bob Tustin and Don Apps. The last time I saw Bob was six days ago. On that day Bob and Mike Walsh left the group near the Elk-Ucona Pass with plans to backpack across to the Golden Hinde, then westerly to Buttle Lake and the Forbidden Plateau. On the previous Friday [August 5], as Bob and Mike were descending The Behinde when Mike sprained his ankle. Bob made sure that Mike had sufficient food and was comfortable, then continued alone over the Marble Plateau and down the new trail, arriving at Buttle Lake Saturday night. All day Sunday Bob was busy signaling and calling to attract the attention of fishermen to take him across the lake. In the evening Jim Boulding from Strathcona Park Lodge was passing by in his boat and came to Bob’s rescue. Arrangements were made for a helicopter to pick Mike up from the south-easterly ridge of the Golden Hinde. Bob and Don Apps left Mt. Becher at 4 p.m. on Monday and walked the 18 miles by way of the Becher Trail and with a flashlight to Circlet Lake.

Participants: Mike Hanry, Ralph Hutchison, Ron Facer, Bob Tustin, Syd Watts, Mike Walsh, Elizabeth and Patrick Guilbride, Doug Jones, Gregg Shoop and his girlfriend, Doreen and John Cowlin, Ray Paine, Dave Birch.

The helicopter flying climbers to Elk Pass, July 30, 1966 – John Cowlin photo.

Climbers (L to R – Doug Jones, Mike Walsh, Bob Tustin) in the upper branch of the East Elk River below Rambler Peak, 1966 – Bob Tustin photo.

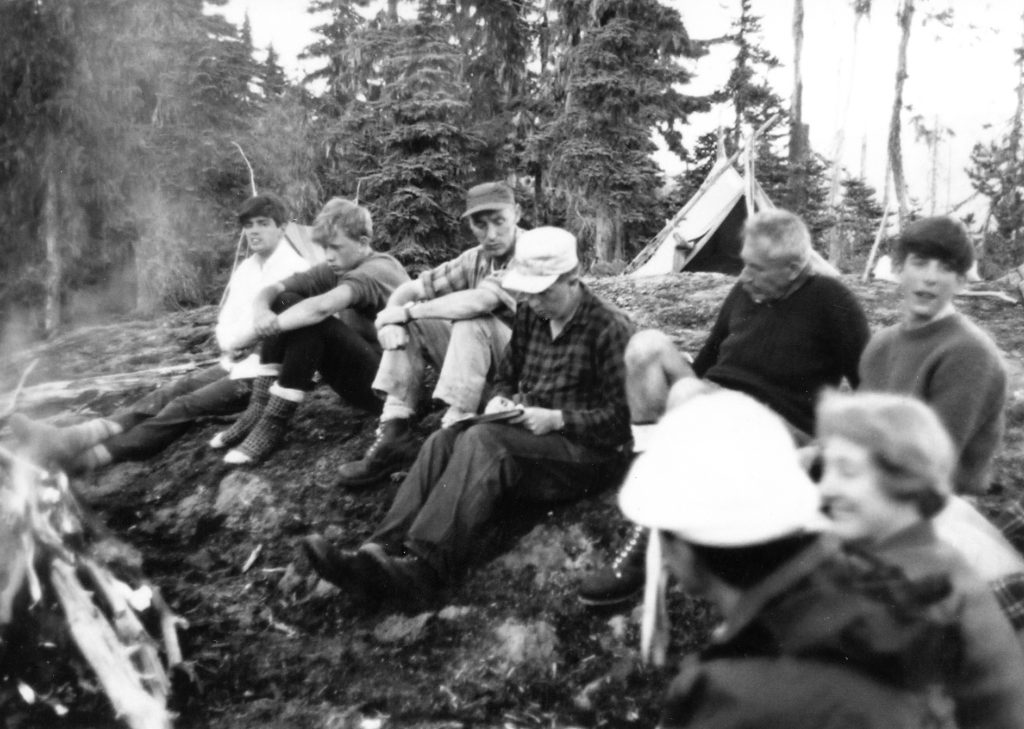

Syd Watts (hat), John (writing) and Doreen Cowlin (lower right) and others at camp on Elk Pass, 1966 – Bob Tustin photo.

Bob Tustin standing on the summit of Rambler Peak, 1966 – Bob Tustin photo.

John and Doreen Cowlin sitting on the Southeast Summit of Mt. Colonel Foster, 1966 – Bob Tustin photo.

Bob Tustin and Ron Facer glissading off Rambler Peak, 1966. Bob Tustin photo.

Copter Rescues Climber

Flyer Plucked off Mountain

Reported in The Vancouver Sun Wednesday, August 10, 1966. p.10.

COMOX—An injured airman was plucked by helicopter from a 4,200-foot mountain ledge near here Monday after spending two nights alone on the mountain. Leading aircraftman Michael Walsh, 21, sprained his foot while climbing with a friend [Friday August 5]. The friend, civilian Bob Tustin, hiked down the mountain to give the alarm while Walsh waited for rescue. “It was a difficult rescue job because the country around there is so rugged,” said Lieutenant Commander E.L. Hauff, pilot of the U.S. coast guard helicopter which picked up Walsh. The U.S. coast guard had to be called in to help by RCAF Comox because the only RCAF helicopter was out of service. The U.S. helicopter arrived at about noon Monday at Walsh’s mountain camp site above Burman Lake, 33 miles west of Comox. “We could not set down there because it was so rocky,” said Hauff. “As soon as we arrived, we saw Walsh standing beside his tent and waving at us so we knew he could walk. We lowered a steel rescue basket down to him, he climbed in and we hoisted him into the plane.” Hauff said the young man appeared to be in good condition and good spirits and received medical treatment on the flight back to Comox from a pararescue crew member. Walsh, who is stationed at Comox air force base, comes from Shediac, New Brunswick. He was treated at the base hospital for a severely sprained foot and sent home on leave.

Mountain Climber Undaunted by Fall

Reported in The Vancouver Sun Thursday, August 11, 1966. p.55.

COMOX—LAC Michael Walsh says he will be back climbing mountains this weekend. A 30-foot fall, a badly sprained ankle and two nights alone on a mountain haven’t discouraged he eagerness for climbing. “I’ll hobble off somewhere this weekend and climb a few mountains,” Walsh, 21, said Tuesday in a telephone call. Walsh was picked up by helicopter from a 3,700-foot mountain ledge in Strathcona Park on Monday after spending two nights alone on the mountain. “Bob Tustin, a friend of mine, and I were climbing the west peak of the Golden Hinde [The Behinde] west of Buttle Lake on Friday [August 5],” said Walsh. “We were about the 6,200-foot level when I slipped and fell about 30 feet onto rocks. Then I slithered about another 100 feet down the mountain. My ankle hurt badly but, with Bob’s help, I managed to make it to about the 3,700-foot level. I thought I might be able to walk by morning, but I couldn’t. So – it was Saturday morning then – Bob started to hike out on his own to get help. I had a tent and a fair amount of food. It rained all day Sunday, but I made out all right.”

Alpinists Open Trail for Public

Reported in The Daily Colonist Sunday September 18, 1966. p.12.

By Alec Merriman

The people who roam over 130 miles of Strathcona Park mountain ridges and climb the highest peaks on Vancouver Island are now building a six-mile-long trail that will bring the alpine areas within reach of just ordinary recreationists. The Marble Plateau Trail will take recreationists from Phillips Creek on the west shore of Buttle Lake to the Marble Plateau, above the timberline to the 5,000-foot level. There recreationists will find meadows filled with alpine flowers in late July and early August, plenty of browsing deer and a myriad of more than 20 small unnamed lakes, which may or not contain trout, but which could easily be stocked. Island Mountain Ramblers have undertaken construction of the trail as its own special centennial project. Membership of that club comes from all over Vancouver Island.

Flowers in full bloom on Marble Meadows 1970’s – Syd Watts photo

Big Project

President is John Cowlin of the Saanich engineering department, who heads the Outdoor Club of Victoria which often joins forces with the Ramblers for ambitious undertakings. From Phillips Creek to Marble Plateau is about two miles as the crow flies, but will be six miles by graded trail. Club members have already completed about 1½ miles of the trail which will be a three or four-year construction project. It will be a series of switch-backs to climb 4,200 feet in four or five hours at an easy climbing rate for the average recreationist. The Phillips Creek start of the hiking trail has already been marked by a rustic sign and the new Strathcona Park Western Mines road down the east shore of Buttle Lake will provide an easy jumping-off point by boat from the proposed campsite, adjacent to the Western Mines townsite at Shepherd-Ralph River.

Ideal Campsite

Phillips Creek is a primitive provincial campsite across the lake and a mile or so north of Shepherd-Ralph River. The provincial parks branch has given approval to the club to build the new trail. The parks branch is working on another Strathcona Park Trail at Wolf River on Buttle Lake, close to the northern boundary of Strathcona Park and has finished about one-quarter mile of the trail. Mr. Cowlin says Marble Plateau’s score of lakes and little clumps of trees make it an ideal spot for a primitive campsite. Because of the limestone formation in the ridges there are plenty of fossils for rockhounds and collectors to find. In season the meadows are a mass of alpine flowers – blue woolly lupins, yellow arnica, purple mountain daisy, orange paintbrush and yellow monkey flower, to mention a few of the more prolific varieties. From Marble Plateau there is ample opportunity for more ambitious mountain rambling. Marble Peak, 5,300 feet high may be reached in a four-hour hike there and back with no special equipment required, although it would require some scrambling. Mt. McBride, 6,829 feet high, makes a 12-hour return trip and it is a walk all the way. The Island Mountain Ramblers are marking the route with tape as they design the properly graded and engineered trail. They have marked the route for about half a mile beyond the 1½ miles of completed trail. From there hikers can follow the ridge to the Marble Plateau. Volunteer workers plan to complete the trial mile by mile as they go, not to build a rough trail first and then complete it.

Several Trips

The Island Mountain Ramblers held several work parties on the trial this summer, but that hasn’t stopped them from making several trips and assaults on Strathcona park’s mountains. On the Labour Day Week-end Mike Walsh of the Comox Air Force base made the top of Elkhorn Mountain, second highest peak on the Island and reputed to be the most difficult of the high mountain peaks to climb. It has probably only been climbed six or seven times before, two of these last year. The Golden Hinde, 7,219 feet, is the highest on the Island, but comparatively easy to climb,

Long Climb

Don Apps of Cumberland and Doug Jones of Courtenay were with Walsh on the trip, but only Walsh got to the top. Earlier this year a party of Island Mountain Ramblers climbed 5,997-foot Puzzle Mountain with four of them—Doreen and John Cowlin of Victoria, Keith Morton of Courtenay and Syd Watts of Duncan—making the top. Puzzle Mountain is south of the Elk River Road in Strathcona Park and is reached from the next ridge west of Elkhorn Mountain. The climb took 13½ hours. In August, the Ramblers climbed 7,000-foot Mt. Colonel Foster, 6,900-foot Rambler Peak, 6,400-foot El Piveto Mountain marking the first time the latter mountain has been climbed by anyone on record. The Comox District Mountaineering Club has spent this summer marking trails and special places of interest in the Forbidden Plateau country as its centennial project.

Island Mountain Ramblers, Doreen Cowlin of Victoria, Sydney Watts of Duncan, and Frank Foster of Vancouver, look across at 7,190-foot Mt. Elkhorn. — (John Cowlin photo)

1967

ACCVI executive:

Chair – Dudley Godfrey

Secretary – Kathleen Tuckey

Events:

July – Herb Warren, Joyce Clearihue, Ruth Masters, Vi Chagranes, and Phyllis and Bill Hill are part of a large Victoria Outdoor Club trip to Hansens Lagoon.

July – Ralph Hutchinson and others make the 1st ascent of Mt. British Columbia as part of the Yukon Alpine Centennial Expedition.

July – Paddy Sherman and others make the 1st ascent of Mt. Manitoba as part of the Yukon Alpine Centennial Expedition.

Section members who passed away in 1967: Alan Campbell, David Gillies.

He Climbed Every Mountain Forded Every Stream

Alan Campbell Surveyed the Rocky Mountain Boundary between Alberta And British Columbia

Reported in The Daily Colonist (The Islander section) Sunday January 8, 1967. p.4, 5, 6.

By Norman Senior

Locating the exact position of the mountain peak border was a tremendous undertaking carried out half a century ago by a Boundary Commission. The man who knows most about it, who spent 12 years on the project, and who almost literally “climbed every mountain, forded every stream,” between the United States border and the point where the inter-provincial boundary leaves the mountain chain to follow the 120th meridian northward, is now living in quiet retirement at 1128 Dallas Road in Victoria. He is Alan J. Campbell, former chief topographer for British Columbia. In the technical sense he retired from the provincial government service about 15 years ago, but so valuable in this knowledge of British Columbia’s mountain terrain that he went right on taking out field parties for the survey branch for long years afterwards. Colleagues say no man living knows more about the Rocky Mountains and the mountains of British Columbia than A.J., as they habitually call him. The surveys that he has conducted over almost every part of the province. In locating, marking and mapping the Alberta-British Columbia boundary in the 12 years from 1913 to 1924 the surveyors used a method not long previously introduced into this country by the famous Dr. Edward G.D. Deville, Surveyor General of Canada. It is known as phototopographical surveying and although the system was first employed in other countries the Alberta-British Columbia boundary survey stands as unquestionably the most comprehensive project to which it has ever been applied. A serpentine line whose extremities lie 350 miles apart as the crow flies has so many sinuosities that the ground covered by the survey would be several times the straight-line distance from point to point. The 12 years undertaking involved up to five months a year in the field, with the remainder of the time spent in the studies or office reducing the photographic evidence and field notes to definitive maps. A legal description of the boundary had been established many years previously, prior even to confederation, by an Act of the British Parliament. It is found in the Act of 1856 writing the crown colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, the centenary of which event the provinces recently celebrated in colorful ceremony. The territorial limits of British Columbia are defined as follows:

“1. Until the Union, British Columbia shall comprise all such territories within the dominion of Her Majesty as are bounded on the south by the territories of the United States of America, to the west by the Pacific Ocean and the frontier of the Russian territories in North American, in the north by the 50th parallel of north latitude, and to the east by the Rocky Mountains and the 120th meridian of west longitude . . .”

“2. After the Union, British Columbia shall comprise all the territories and islands aforesaid and Vancouver Island.”