1955

ACCVI executive:

Chairman – Bill Lash

Secretary – Margery Thomas

Executive Committee – Connie Bonner, Cyril Jones, Patrick Guilbride, Noel Lax, Mabel Duggan

Events:

The Vancouver Island section had a very satisfactory year of climbs, hikes, photography and skiing. The section was well represented at the ski camp and again at the summer camp. All of the club’s outings were followed without cancellations or changes, regardless of the weather. An average of twelve members attended each climb and on three occasions we were joined by members of the RCAF rescue group from the station at Comox.

The first outing of the year was a ski trip to Panorama Ridge in Garibaldi Provincial Park. The weather was clear and cold and the snow was deep powder.

March 26 – Club’s annual banquet held at ??? Raymond Patterson was the guest speaker showing slides of the “Dangerous River” the Nahanni which is also the title of his acclaimed book. Forty-four members and guests attended.

May – Mt. Tzouhalem’s rocks provided good pitches for the May rock school.

May 21/22 – Club trip to Mt. Porter. Members camped by the Sproat River Falls.

June – Club trip to Mt. Joan (Beaufort Range).

July 1/2/3/4 – A club trip to Dosewallips State Park in Washington to climb Mt. Constance. Twenty members attended the trip.

July – A club trip to Sansum Narrows on the ketch Tzu Hang, by Miles Smeeton, was well attended.

Miles and Beryl Smeeton on their ketch Tzu Hang – Clio Smeeton photo.

The ketch Tzu Hang in Victoria Harbour – Clio Smeeton photo.

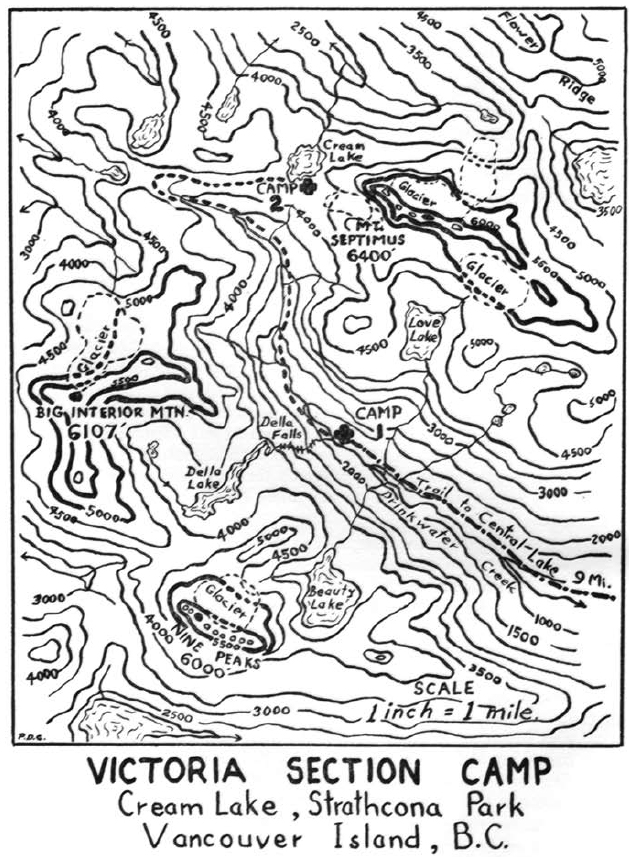

August 27 to September 4– Club camp up the Drinkwater Creek where Nine Peaks, Mt. Septimus and Big Interior Mountain were climbed. As far as we know, Mt. Septimus had only been climbed once before. Eleven members attended the camp.

October 8/9/10 – A club trip to Mt. Arrowsmith for the Thanksgiving Weekend. Six members attempted to climb the mountain, but rain, snow, sleet and Hurricane Hazel’s little brother drove the climbers back to a cabin which was very kindly lent to the club by the Alberni Ski Club.

November – The annual meeting of the section was held at the home of Muriel and Aileen Aylard. The club welcomed two prospective members Ulf and Adolf Bitterlich who showed slides of their two-man assault on Mt. Waddington in August.

December 24 – Elizabeth Larrett and Patrick Guilbride, both Active and Life members of the section, were married on Christmas Eve.

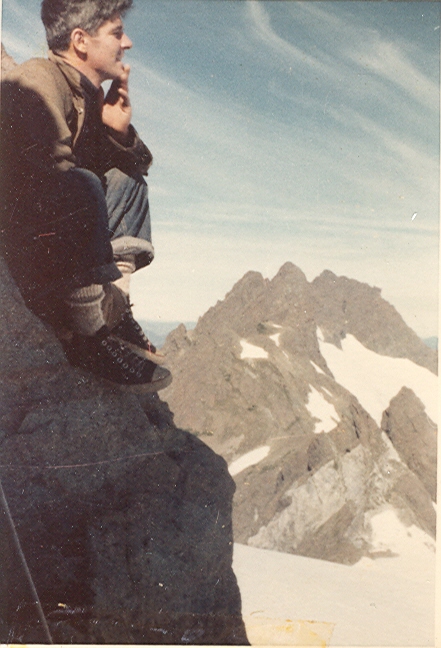

Patrick and Elizabeth Guilbride in 2001 – Lindsay Elms photo.

The April Ski Camp was at Glacier with the Vancouver Island section having the most attendees and the most boil-ups.

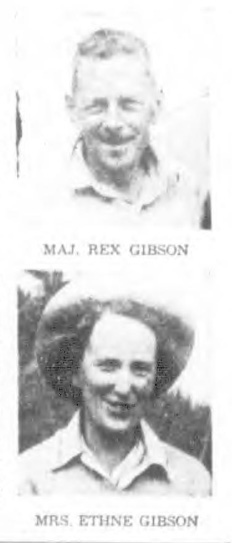

Section members who attended the ACC general summer camp at Mount Robson July 25 to August 7: Mabel Duggan, Judith Davis, Ted Goodall, Ethne Gibson, Rex Gibson, Sylvia Lash, Bill Lash, Elizabeth Larrett [Guilbride], Fred and Edith Maurice, Mark Mitchell, Margery Thomas

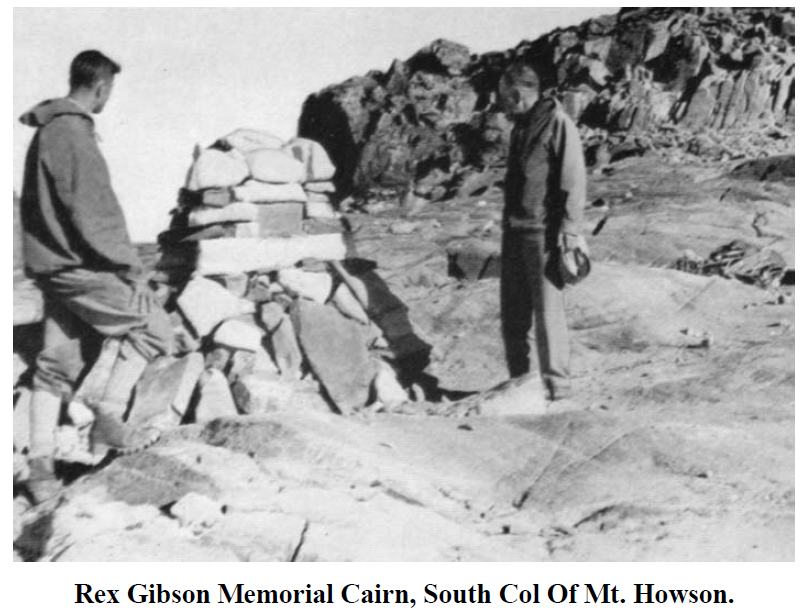

Mountain Climber Honored

Reported in The Vancouver Sun Wednesday February 9, 1955. p.10.

OTTAWA—A Port Alberni immigrant has been recommended for a humane association award for three daring mountain rescues carried out within five months last year. The immigrant is Ulf Bitterlich, formerly an experienced mountaineer in the German Alps and the Urals. His first rescue was carried out on July 3 on Mt. Septimus near Alberni, when two climbers fell through a snow bridge, killing one. Bitterlich descended to the bottom of the 200-foot crevasse to bring up an injured girl, Alma Currie> he brought her down the mountain and then returned to bring out the body of his friend, Ralph Rosseau. On October 11, Bitterlich was climbing on Mt. Arrowsmith with his brother when they heard what sounded like an aircraft crashing. The German climber sent his brother to summon the RCMP and spent the rest of the night in an unsuccessful attempt to find the wreck. It was found the following day after he had been joined by a search party. Two weeks later the Alberni lumber workers climbed Mt. Arrowsmith at night in a blinding storm with winds up to 70 miles-an-hour to bring down a climber with a broken lag. Bitterlich, with one companion, climbed 6,000 feet in half the normal time to bring down Charles Faulkner.

Mountaineer Hero of Three Rescues Proposed for Top Humane Award

Reported in The Vancouver Province Thursday February 10, 1955. p.28.

A Port Alberni mountaineer who played the leading role in three mountain rescue bids in five months has been recommended by Port Alberni citizens for one of the top wards of the Royal Canadian Humane Association. The association is now considering what action to take. The climber is Ulf Bitterlich, who came to Canada from German in 1951. In July he was climbing Mt. Septimus on Vancouver Island with three friends when two of them fell through a snow bridge into a rocky gully. Ralph Roseau, Port Alberni teacher, was killed. Bitterlich rescued the survivor, made the rest of the party comfortable, then tramped many hours to bring help. In October he was the leader of a climbing party which found the wreck of an RCAF Expediter on Mt. Arrowsmith. Four men died in the crash. Bitterlich and his brother Adolf stayed at the scene with RCAF men to bring the bodies and equipment out, and cut a staircase in ice to help parties reach the spot. And two weeks after he left the mountain, Charles Faulkner of Victoria broke his leg near the summit of Arrowsmith. Bitterlich climbed to the scene at night, then ended up with two injured on his hands, when falling rock injured his companion, Leo Lynn. Bitterlich, a former member of the German mountain rescue organization, supervised all the rescue work.

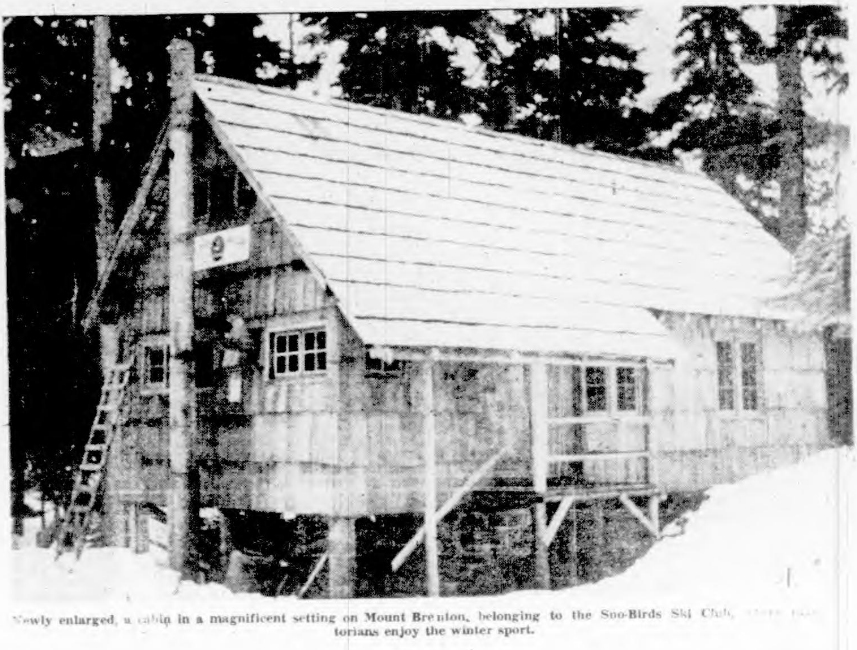

Ski Club Moves for Park at Mt. Brenton

Ask Royal Commission Set Aside 2,500 Acres For recreation Area

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Monday March 28, 1955. p.13.

Victorian Sno Birds Ski Club today recommended to the Sloan Royal Commission that a 2,500-acre park be created on Mount Brenton near Chemainus. Club official Anthony Emery presented a brief to the commission, asking that the provincial government take over the tract “for recreational use of the citizens of the province.” The land is now owned by Van-West Logging Co., but Mr. Emery said his group is of the opinion “they would be prepared to negotiate for its outright sale at a reasonable figure.” The Ski Club has already constructed a large cabin at Silver Lake, and operates a 500-foot ski tow from January to May, Mr. Emery said. He told Chief Justice Gordon Sloan there is no provincial park on Vancouver Island providing skiing facilities similar to those available at Mount Brenton. Mr. Emery said the proposed park’s location puts it in a central position to 90 percent of the residents of Vancouver Island. He said, it possesses great natural beauty, with a view from the Brenton Bluffs across Georgia Strait “unparalleled on the southern half of the Island.”

Sno-Birds Win First Sanctioned Meet on Mt. Brenton

Reported in The Daily Colonist Tuesday March 29, 1955. p.9.

Sno-Birds Win First Sanctioned Meet. Victoria Sno-Bird Ski Club Sunday scored a narrow downhill tournament victory over the Nanaimo Ski Club on the Mt. Brenton slopes in the first Western Canadian Ski Association sanctioned competition ever held on Vancouver Island. The active Victoria club, which operates a 500-foot ski tow in the Mt. Brenton area, has recommended to the Sloan Commission on forestry that a 2,500-acre park be established on Mount Brenton. Club spokesman Anthony Emery presented a brief to Commissioner Chief Justice Gordon Sloan asking that the province buy the land for recreational purposes from the Van-West Logging Co. Members of the winning team are, left to right, Bob Thate, Art Davies, Bob Davies, Herta Von Barlowen, Leo Pike and Erwin Egger.

Immigrant Wins Medal for Bravery

Alberni Man Honored for Daring Rescue On Mountainside

Reported in The Vancouver Sun Friday June 24, 1955. p.27.

A German immigrant, hero of Vancouver Island mountain-top rescue, heads for the list of Canadians honored today for civilian bravery by the Royal Canadian Humane Society. Named recipient of the eleventh silver medal in the society’s 61-year history is Ulf Bitterlich of Port Alberni. Bitterlich, a modest, shy 26-year-old, won top recognition for his role in the rescue of Victoria climber Charles Faulkner from the 6,000-foot Mount Arrowsmith, highest mountain on Vancouver Island, last November.

Young Alberni Alpinist Wins Medal for Heroism

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Friday June 24, 1955. p.25.

Alpine climber, Ulf Bitterlich of Alberni has been awarded the Royal Canadian Humane Association’s prized silver medal for bravery for his outstanding example of heroism in the rescue of Charles Faulkner Jr., of Victoria, from the summit of Mount Arrowsmith last fall. The silver medal topped the list of awards to Canadians for heroism made by the association at Hamilton, Ontario, today. The medal is the 11th to be awarded by the organization since its inception 62 years ago. Bitterlich, a German immigrant who came to Canada shortly after the war, received the medal for the part he played in saving the life of Faulkner, who fractured his leg in a fall from the peak of Arrowsmith. Faulkner, an expert climber, fell and tumbled onto a treacherous ledge overlooking a sheer 200-foot precipice. He was unable to move because of his leg injury and he lay only a few inches from the precipice.

Night Exploit

Bitterlich and a companion Leo Lynn, climbed the 6,000-foot peak to assist the injured climber. It was night when the rescuers got there. Seventy mile-an-hour winds whipped at them and rocks fell constantly from overhead. One hit Lynn on the head injuring him fairly severely. They treated the injured climber, but were forced to wait until daylight before attempting to move him with the assistance of a rescue party. Bitterlich worked strenuously for 45 hours on the rescue, playing the major part in the operation.

Long Exposure

Faulkner was finally taken down the mountain with great difficulty after spending two nights exposed to lashing winds and rain on the slopes of the peak. He is still recovering from his leg injury. Bitterlich is regarded as one of Vancouver island’s best mountaineers. He took part in one other mountain rescue early last summer.

Seven Higher Peaks

Reported in The Vancouver Sun Thursday June 30, 1955. p.4.

Editor. Sir,—On page two of your issue of June 24 you print an article of a German immigrant hero receiving a silver medal for having rescued a Victoria climber, Charles Faulkner, from the 6,000-foot level of Mt. Arrowsmith, “the highest mountain on Vancouver Island,” last November. I’d appreciate it if you’d tell me how one could effect a rescue at the 6,000-foot level of a mountain which has a maximum altitude of 5,976 feet? There are seven mountain peaks on Vancouver Island higher than Mt. Arrowsmith. The highest peak on Vancouver Island is the Golden Hinde, otherwise known as “The Rooster’s Comb.” The Golden Hinde is named in honor of the ship in which Sir Francis Drake made his epic voyage to the Pacific in the days of Good Queen Bess. The other mountains which are higher than Arrowsmith are: Elkhorn Mountain, 7,200 feet; Victoria Peak, 7,095 feet; Mt. Albert Edward, 7,000 feet; Mt. Alexandra, 6,394 feet; Crown Mountain, 6,082 feet; Mt. Jutland, 6,000 feet. Mounts Albert Edward, Jutland, Elkhorn, Golden Hinde, Crown and Alexandra Peak are all situated in the Strathcona Park area and Forbidden Plateau region. The Golden Hinde rises from the shores of Burman Lake and is in a very beautiful setting dominating Strathcona Park.

Samuel J. Hartnell

ACCVI Trip to Mount Constance, Washington State

Reported in the personal diaries of Geoffrey Capes, 1-3 July 1955.

July 1. Friday – Phyllis dropped Katherine and me in front of the store about 8. Ken Stoker came along about 8:15 with Corporal Bill Chapman. We piled our stuff in the middle of the back seat. Katherine and I sat on each side and were quite comfortable. With a stop for gas and a stop for coffee on the Malahat, we arrived at the dock in Victoria about 12:15 in time to get in the line up for the State of Washington ferry, the “Kalakala”. It rained at one point on the way. We met the rest of the Victoria Section of the Alpine Club there. We had lunch on board and arrived in Port Angeles in about 1½ hours. We spent about an hour there while Ken and Bill did some shopping. It is a very busy little town, hardly a parking site and sidewalks full of people. Highway 101 running East as far as Sequim through more or less flat farming counties. We noticed one or two big herds of cows. Turning south at Discovery Bay the road runs with mountainous country all the way. It rained on this section of the journey. Before turning off on the road that parallels Dosewallips River, we ran for a short distance along the shore of Hood Canal. One of the sights of the journey from Port Angeles was the Rhododendrons. The blossoming was just about over. On the lower part of the Dosewallips River, the foxgloves made quite a showing. There were scattered dwellings for the first few miles then the road became rougher and there were some very steep grades, particularly just before reaching the camp site, 13 miles from the main road. It was about 65 miles altogether. The camp site is on a wooded flat alongside the Dosewallips River. Each site having tables and bench, and a fireplace made of precast cement and grating. There must be a hundred of these sites, and by the time we left every one was occupied. Ted had arrived and had the tent up. I got an air mattress and sleeping bag laid out, then we cooked supper. Ken and Bill erected their RCAF emergency tent and everyone of our party came to look at it. There was a sing song during the evening. I turned in about 9:45.

July 2, Saturday – Cyril Jones gave his rooster call about 4. The camp roused itself by about 4:30. It was 6:30 before we started. We drove back along the road to where the Lake Constance Trail leads up the mountain. The trail followed a noisy creek. It was very steep the whole way to Lake Constance. I suppose about 4,000 feet. We followed round the small lake and crossed the creek. Snow lay here in the timber. In a short time we emerged on to snow fields. I had “Skreen” on my face and put on dark glasses though the sun was not very strong. Except for one or two islands of rock, the snow fields covered everything and we rose steadily. We paused for lunch on one of the rocky islands. Where the snow steepened, I went on a rope led by Syd Watts. Katherine, Ted and a chap called Pete Thomas also. Katherine and Pete had no ice axes. The snow was hard. We came to a gulley free of snow. Here we noticed fresh snow from yesterday and there were small icicles hanging from the walls. Visibility was poor. It was difficult. In parts impossible to see the mountain tops. Ted elected to stay there. If there had not been a very cold wind blowing, I would have done so too. We traversed a steep snow slope for some distance then climbed up the slope to a long scree and rock gulley. Up this on to more snow. Turned left to where one of the peaks of Mount Constance came in view. Several times I had told Syd I wanted to quit and wait for the return. My thighs were giving trouble however, I went on. Those we found had left their ice axes so we followed suit. We scrambled up a rock slab and came to rest on a kind of terrace. The stronger climbers were above us trying to find a route to the summit. The rest of us waited in a bitter wind. I took the opportunity to have a short sleep. This went on. We cannot have been more than 150 feet from the summit of the 7735-foot mountain. A route was not found. We heard later we should have gone through a crack, made a finger traverse with an 800-foot drop below. About 3:15 we started down. On the way up just after we started on the traverse, Pete, who had no ice axe, slipped. He did not go far as the snow was soft. I had a coil round my ice axe. At the head of the gulley we unroped and for a thousand feet or so slid down the scree. The lower part was rougher. By the time we got to the long snow fields, only Katherine and I were left. Pete made faster progress and disappeared. Rx Gibson and Syd Watts soon passed out of sight. After Katherine and I had gone some distance we were surprised to find Cyril Jones catching us up. He was very tired the same as I was. The snow was safter than it had been in the morning. I was rather pleasant. There was no wind. There was a slight fog and little visibility. In due time we arrived at lake Constance. We stopped for a drink of water. Once off the snow Katherine went ahead with two of the others. Cyril and I dragged our weary bodies down the steep trail. I shared what was left of lunch. We stopped often to rest. Twenty men, boys and women must have passed us going up and there were one or two lots of people camping at the lake. At 8:50. About an hour later than everyone else we emerged on the road to find Syd waiting. Margery Thomas and Dr. Mark Mitchell who had not been with the twenty that invaded the mountains, had hot soup for us. Dr. Mitchell had lighted all the cooking fires. We had a leisurely Supper. I managed to eat quite a lot. It was wonderful to wrap with the sleeping bag.

July 3. Sunday – Sunday up about 7:30 not feeling too bad. A leisurely breakfast. Got everything packed up and as Ken did not appear to be nearly ready, I had a look around. Spoke to the Ranger and walked about half a mile up the trail pasted her cabin. I met some boys with fishing rods. Our party as usual then had to leave. We stopped to photograph the falls then went on. It was raining and it continued to rain all the way to Port Angeles. Soon after emerging on the highway, we stopped to lunch at the Olympic Inn overlooking the Hood Canal It is a nice place, magazines scattered about. Strangely enough the July copy of the National Geographic magazine had an article on the Olympics. Ken did not waste time driving through the steady rain to Port Angeles as the ferry does not reserve places for cars. One has to take a chance on a line-up and it is usual to be in place an hour before the Ferry sails. We were only half an hour but we got on the last row. Although there was no wind the “Kalakala” rolled in the swell from the pacific. Had a cup of tea on board. The customs asked a few questions in Victoria. It had been raining in Victoria, but it was now fine. We took the new unfinished Highway to Goldstream. Stopped for a sandwich and a cup of tea on the Malahat. Ken does not like being in a line of cars and he maneuvered his Morris, that we passed everything on the road. Somewhere around Chemainus an old panel truck was parked on the side of the road with smoke and steam enveloping it. A number of cars were present. We did not stop. Ken and Bill had to get a picture of the beautiful sunset so arrived in Courtenay. We crossed the Dyke. Ken then drove Katherine and me home. It had not rained in Courtenay. We arrived about 9:30.

Included in the party were Geoffrey Capes, Katherine Capes, Syd Watts, Cyril Jones, Rex Gibson, Bill Chapman, Mark Mitchell, Margery Thomas, Ken Stoker, Peter Thomas.

Rain, Snow End Alpinists’ Bid on Mount Robson

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Monday August 8, 1955, p.3.

JASPER, Alta.—Members of the Alpine Club of Canada Sunday described their first attempt in 30 years to scale 11,068-foot Mount Robson as a “disappointment.” Rain and fresh snow which fell almost continuously during the first 11 days of the two-week camp made the climb to the summit too dangerous. Friday another party led by Major Rex Gibson of Victoria, scaled The Dome, 10,098 feet, an outlier of Robson.

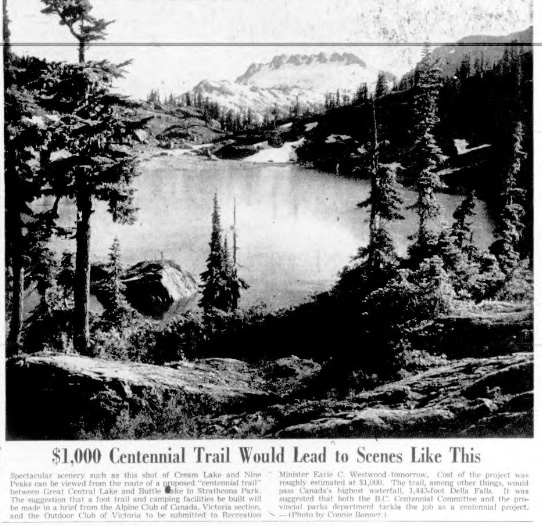

Buttle Lake

Reported in The Daily Colonist Friday August 12, 1955. p.5.

I get sick and tired reading all the phoney stuff about Buttle Lake by the power commission. My home is at Buttle Lake and I have lived there for 28 years. The government says that only millionaires with planes can get to the lake. Bunk! The cars at the foot of the lake have been so thick the last three summers that I have been thinking of opening a parking lot. A lot of them tow their boats on trailers and I have seen over 30 strange boats on my end of the lake at one time. Thousands of people have come in to the lake since I have lived here—very few of them in planes. We had a good trail for pack horses for more than 20 years; the government built it and kept in in condition. The Elk River Timber Company logged over it and while they were logging the visitors came in on the ERT speeders and work trains. When the Elk River Company was forced to stop logging in the lake, they did not open the trail. During the six years that the government kept the trail closed, we had to walk out to Upper Campbell on the logging railroad. Then the power commission thought they could build a dam here, and build a good auto road to the lake. If the crowds don’t stop coming, I’m going to have to move. Guess I’ll have to move anyway, because I’ve seen timber cruisers in here the last three years that it looks like a cinch, they are going to log out the timber. One of the cruisers told me that there was over 700,000,000 feet—mostly Douglas fir—that could be pulled into the lake. One thing I have learned for sure during my 40 years in B.C. is that where Douglas fir is, loggers will go—park or no park.

Harry Roger

Buttle Lake, B.C.

Save Strathcona Park! Slimy Chaos Alternative to Beauty

Reported in The Daily Colonist Friday August 19, 1955. p.1. & 2.

By Roderick Haig-Brown

There are two alternatives in the future of Strathcona Park and Buttle Lake. The first is mud and slime, stumps and debris, chaos of logging, hazard of fire. It will be followed by years of blowdown creeping gradually back into the tall forest, creating new fire hazard, building logs and brush and second growth. It will mean destruction of natural spawning beds, flooding of flats that are life itself to the wintering elk herds, drowning of swamps and deciduous trees that are food for beaver and ruffled grouse. It will bring about an enormous and destructive change to every natural balance within the park boundary. The second alternative is an untouched, unchanged natural area, more beautiful than any other on the island, true to the original cycles and balances as no other area can ever be. And the difference between these two alternatives is something less than fifteen feet of water; perhaps less than ten feet. If the lake and the park are saved as they must be, what is their future? It has been said many times in the present controversy that the park is inaccessible, that the public cannot get into it. Only a few millionaires fly in there and keep it to themselves. This is a lie. Until the old trail was logged over the park was always accessible to the public. Even after that, people who had been going in for years continued to go in, over the abandoned railroad grades. Within the past year or two, people have gone in by hundreds, over the narrow twisting logging road that is too often barred by gates. But all this is not the measure of the lie. The true measure of the lie is in the suggestion that any lake lying thirty miles back from salt water and only 700 feet above it could possible be called inaccessible. That is a lie so obvious that it should never have fooled anyone. But it has fooled people. Any government of the past ten years awake to its responsibilities could have built a good road into the lake for less money than was spent on the old trail. And the people who foster the lie know this very well. If you don’t choose to cross a street, it is true that you won’t get to the other side; but that doesn’t make it inaccessible. Strathcona is the most readily accessible major park in British Columbia. Building a road into Buttle Lake is a cheap and simple operation by any standards. It is long overdue and it is a natural first step in the development of the park. The present logging road is not a good enough entrance to a great provincial park, and the public must not be left dependent upon the good will of logging companies. It is equally urgent that the park boundaries be changed to take in the full length of Buttle Lake and at least part of the new lake that will be formed. This can easily be done by exchange of forest land, since there are valuable timber licenses on the western slope of the park, beyond the high mountains, which could and should be released into management licenses or working circles. Additional funds realized from this must be earmarked to pay for the road and other development. At the end of the road a concession will be granted for boat rental and for a lodge and cabins, to be built under supervision of the Parks Division. Development farther up the lake should move more slowly; safe and simple campsites near the best beaches are the first obvious need. Trails should be built on the west side of the lake up Wolf, Phillips and Myra Creeks to the alpine country around the Golden Hinde. On the east side of the lake it is a relatively simple matter to build a trail up Shepherd’s Creek and Ralph Creek into the Forbidden Plateau. And sooner or later there will certainly be a road through the pass from Price Creek, at the head of the lake, to the Alberni’s. This is a skeleton plan of simple and low-cost development that would give Vancouver Island its first and only large-scale park. Within two or three years of such development the park would be used by thousands of people and other development would follow logically. Buttle Lake with Myra Falls and the magnificent timber flats at Marble, Wolf, Phillips and other creek mouths is far and away the greatest attraction in the park, as well as its only logical route of access. But there is an infinity of lesser attractions—Flower Ridge, Marble Mountain and Marble Lakes, the Golden Hinde and a dozen other great peaks, to name only a few of them—which would eventually be opened up. All this depends on preserving the shoreline of Buttle Lake. There is not one park expert in Canada who can honestly say that the true possibilities of the park can be realized if flooding takes place. The moment a clearing axe is laid to the first tree something wonderful and irreplaceable will be lost forever. No park official will say. None will be allowed to. I learned long ago from a great Chief Forester of this province, the late E.C. Manning, that the civil servants must always suffer silence under errors of the government policy, however serious; the only alternative is resignation and leaving the affair to some lesser man who will say what he is told to day. If this was true in Manning’s day, it is equally true today. The public must judge for itself and speak for itself to have a hope of having its birthright. And what is it all about? A few thousand horsepower in a total over a quarter of a million. Nature provided a 400-foot head at Elk Falls. The commission has taken fifty-eight feet of storage at Lower Campbell Lake. It will be taking another 120 feet or more at Upper Campbell and Buttle. Do we have to crawl on our hands and knees and beg for just ten or twelve feet of this massive storage to save Strathcona Park? Is there not one man in the provincial cabinet with the vision to measure ten feet of water storage against the only wilderness park on Vancouver Island? Is nothing left of the dream men dreamed in 1911, now that it is within realization? Talk can go on forever. It surely will, if the shoreline of Buttle Lake is desecrated. No torrents of talk can change it, nor the dismal figures of a hundred engineers. Ten feet of storage, a few miserable kilowatts of electricity, expendable in neon signs, against the only wilderness park, the only unravaged shoreline of Vancouver Island. We may be a materialistic people, living in a materialistic age, caring little for anything beyond our own time. But surely we can afford this one tiny gesture of generosity to the future, and leave Strathcona Park untouched. All the electric power in the world can never build anything like it again.

Dam to Raise Level of Buttle Lake Will Be Constructed Immediately

Reported in The Daily Colonist Friday August 19, 1955. p.13.

Work will start almost immediately on construction of a 160-foot dam two miles below the outlet of Upper Campbell Lake, which will eventually create one big lake of Upper Campbell and Buttle lakes, and raise the level of Buttle Lake by nineteen feet. But B.C. Power Commission officials said yesterday that the level of Buttle Lake will not be affected until late 1957 at the earliest. Contract to build the Upper Campbell dam was awarded yesterday to Dawson Wade & Co. LTD., for $4,921,875. The BCPC hopes the dam will be sufficiently advanced by November, 1956, that there will be water storage in Upper Campbell Lake available downstream generating plants at Ladore Falls and the John Hart units. Originally expected to be a two-stage development, the Upper Campbell project will now be one continuous effort to provide power as soon as possible. But it will depend on natural runoffs as to how long it takes to fill storage space at Upper Campbell and then Buttle Lake. Power Commission officials hope that by the end of 1957 Buttle will start rising to the new level of nineteen feet above the average high-water level. Before the level of Buttle is raised a twenty-four-foot strip around the lake will be logged and cleared. Final details for this project have to be ironed out with the water comptroller and forest service before tenders are called for the work. All timber affected within the Strathcona Park boundaries will be sold by public auction. The BCPC expects to make an early start on the installation of two 42,000 horsepower generating units at the Upper Campbell dam site and would like to have these in operation by 1957. Roderick Haig-brown, noted Campbell River conservationist and author who has consistently opposed any interference with Buttle Lake on grounds that it would spoil one of the last wilderness areas, and ruin Strathcona Park, expressed surprise last night when he heard a contract had been let to erect the dam to its full height. “They have made a mistake in letting that contract,” he said. “It is quite needless and sloppy handling.” He said it is not yet known how much flooding Buttle Lake can stand; for it is not known how much horsepower the last few feet the lake is raised will generate; and that Vancouver Island will have to go somewhere else for its power soon anyway. “All they have to do is advance the Bute Inlet project by a year and leave Buttle Lake as it is,” Mr. Haig-Brown said. He added “there is no problem in getting power for the Island. Ultimately, we won’t be short of power because we will have to get it from the mainland.”

Leave Awful Mess

He said the flooding of Buttle Lake will leave an “awful mess.” Clearing of the bush, he said, is an impossible task and “if the proper conditions were enforced there would be no dam because the cost would be prohibitive.” But B.C. Power Commission argues the lake will be more accessible to the public as roads will be built. Restriction of the water licence to the BCPC insist that proper campsites are cleared, boat landings built, but access roads constructed. There is a rough road to Buttle Lake now, but it passes through two privately-owned logging company operations, which are sometimes barred by gates. Since the BCPC constructed a rough road to the head of the lake last year, Buttle has been used by the general public more than it has been since the old trail was overgrown and logged over, but strictly speaking, the general public has no right of access by road. Colonist reporters, who flew over Buttle Lake yesterday, observed three or four tents pitched on the lakeshore, but saw no boats fishing in the lake. When the Upper Campbell project is completed, it will bring the Campbell River system up to 322,000 horsepower capacity – 84,000 at Upper Campbell, 70,000 at Ladore and 168,000 at the John Hart plant. The new dam will be earth-fill construction 160 feet high and 1,800 feet long at the top. It will be 1,000 feet thick at the existing river level and 36 feet at the top. About 2,000,000 cubic yards of earth will be used in construction. The generating plant will be on the downstream side of the dam at the west end to which water will be carried through a 22-foot diameter penstock to two 42,000-horsepower units. When the job is completed the storge behind the dam will form one large 30-mile-long lake out of Buttle and Upper Campbell. The power commission will have the job of gathering and removing a tremendous amount of old logs and debris which now lie around Upper Campbell and Elk River valley, which is now a logged-off mess.

Climbing In Strathcona Park

August 27 to September 4, 1955.

Recorded in the Canadian Alpine Journal Volume 39, 1956. p.59–63.

By Elizabeth Guilbride and Margery Thomas

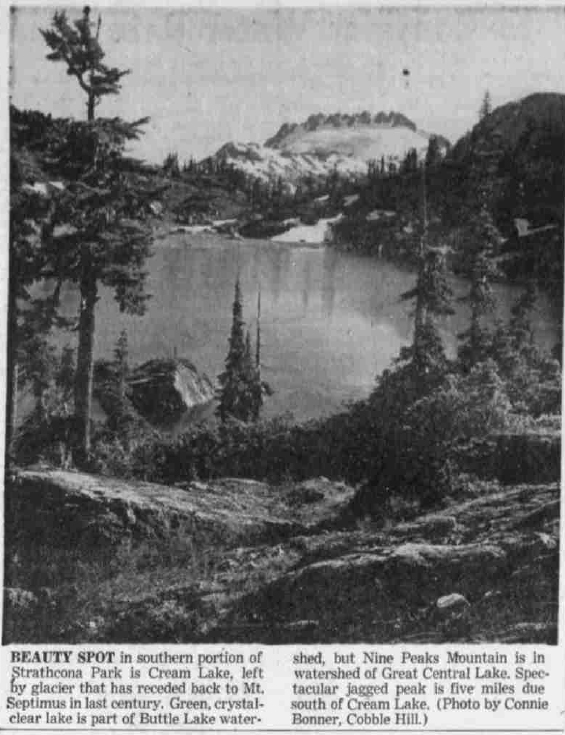

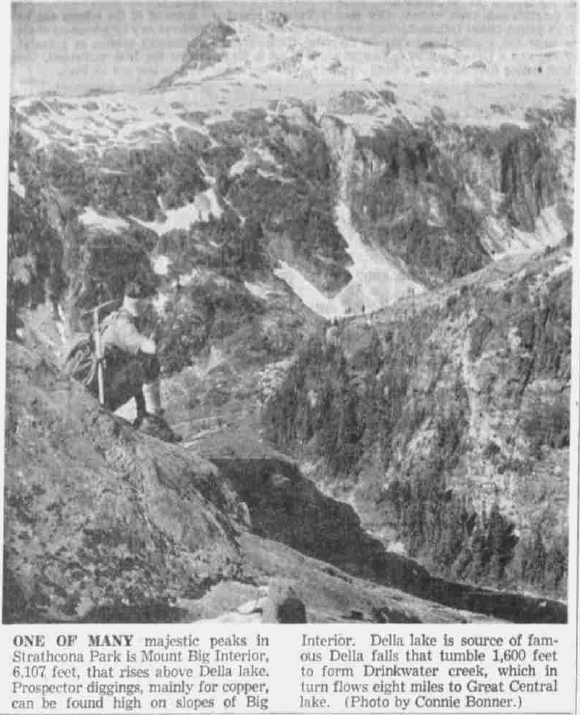

Late in August 1955, eleven members of Victoria section set off for Strathcona park, Vancouver Island, to climb, and to see for themselves more of the beauties of this island. The objective was to climb Nine Peaks (6,000 feet) Mt. Septimus (6,400 feet) and Big Interior Mountain (6,107 feet). These mountains rise steeply from the Drinkwater Valley which lies to the north of Great Central Lake. Though they are miniature mountains they provide interesting climbing and truly alpine conditions. The first campsite, was chosen in advance for its beauty, lay beside Drinkwater Creek at the foot of Della Falls. These falls drop vertically for 1,580 feet and with the lake above them were named after the wife of Joe Drinkwater, a prospector who lived in this valley years ago. Della Falls together with the lesser streams from Love Lake and Beauty Lake form the riotous creek named after Joe. The climbers, three women and eight me, arrived at this campsite at 6 p.m. on August 27. They had left Victoria at 3:30 a.m. on that day, driven 130 miles to Great Central Lake, taken Paddy Burke’s boat for about 20 miles up the lake and walked with heavy packs for 9 miles up the valley to this lovely, sheltered spot. Next day (August 28) the men went back to the head of the lake for the rest of the supplies. Climbing ropes and ice axes, sleeping bags, air mattresses and tents, cooking pots and food for the party for eight days were then assembled at this campsite. On August 29, Nine Peaks was climbed. The route led up beside Della Falls onto the meadows by Della Falls, up the rocks and onto the glacier, round the crevasses and across a snow bridge, over a bergschrund and onto the rocks again to the first summit. Three of the party crossed a col to the second peak then went up more rock to the third, which is the true summit. Below lay Della Lake, Beauty lake and Love Lake and in the distance beyond, Cream Lake could be seen in a scooped-out hollow at the foot of Mt. Septimus. The following day (August 30) a party of four started out to reconnoiter a route up to Cream Lake. Through creek beds and patches of slide alder, they followed the valley nearly to its head and thence went up a gully, arriving at dusk on a small col that overlooked Love Lake. From the col there was a good view of Mt. Septimus and the sight of the fog rolling from the Pacific with the setting sun behind it was especially beautiful. In the morning (August 31), having failed to find a route around Mt. Septimus that would lead to Cream Lake there was no alternative but to climb with full packs up to 5,600 feet then down some fairly steep snow for 1,200 feet to Cream Lake at the foot of the moraine. A beautiful spot for a camp was found beside this small round lake, not cream in color but a deep clear blue. Streams flow into Buttle Lake which lies deep in the next valley. Soon after the four arrived at Cream Lake the weather closed in and visibility was nil. It was uncertain whether the rest of the party would find then until voices were heard through the mist and three more people appeared. No route to Cream Lake with full packs could be called easy, but the second party had found an easier route at the extreme end of the valley and up a tongue of snow to the ridge. The rest of the group arrived the next day (September 1), also having taken the easier route. It took them longer because they had sauntered along admiring the tiger lilies, valerian and wild asters in the valley and the heather-covered ridge dotted with tarns. On September 2 a party of six started out on Mt. Septimus. The mountain, believed to have been climbed only once before [Ralph Rosseau 1947], presented some difficulty in regard to the route. There was no doubt as to which of the seven peaks was the summit. A rope of three went up the most westerly peak and after some tricky and exposed pitches reached the top only to find it was not the true summit. It was too late then to look for another route so they returned to camp at 5 p.m. The other three, Elizabeth and Pat Guilbride and Syd Watts, went up a chimney only to find that it wouldn’t go, so down they went onto the snow to start up another gully from which the second peak was reached without much difficulty. Again they found it was not the top and descended again to the snow and started up another gully farther to the east. About 300 feet below the summit one other member “folded” and was left on a ledge while her companions reached the true summit after a few airy pitches. They were unable to retrace their steps so had to descend again to the snow and climb up to fetch her down. Camp was reached at 9 p.m. Next day (September 3) a party of four climbed Big Interior Mountain in beautiful weather. From the summit were magnificent views in all directions—to the west breakers of the Pacific 20 miles away; to the east the Coast Range and Mt. Waddington; and to the south Mt. Arrowsmith, Klitsa Mountain and Mt. Moriarty were clearly visible. On the last day (September 4), the group walked out to Great Central Lake in blazing sunshine. One of the party was dragging a little and he arrived at the lake after dark. It was discovered that along with his personal stuff and a billy or two he was carrying a large crow bar, a small crow bar and a sledge hammer from a deserted mine 9 miles back They had taken his fancy so he carried them out. During the last days three pairs of boots had been repaired, their soles tied to the upper with cod-line. Several pairs of trousers had been well sutured and probably would not be able to undertake another trip. The climbers themselves after 38 miles of back-packing felt well set up for the winter. We had achieved out objective in the three climbs. We had enjoyed swimming in the lakes and tarns. The food was good and adequate, augmented now and then with blueberries. We learned that Connie Bonner’s art does not stop with the brush and palette but extends to the more practical art of cooking. Her pumpkin powder jam made at Cream Lake camp was greatly appreciated. Except for one evening of fog the weather was fine and clear. The expenses were modest, $10.50 each for the whole trip. It was an excellent trip but we all felt that if we could get a helicopter next year, it would greatly increase our climbing range and capacity.

Included in the party were Elizabeth Larrett [Guilbride], Margery Thomas, Connie Bonner, Syd Watts, Patrick Guilbride and 6 others.

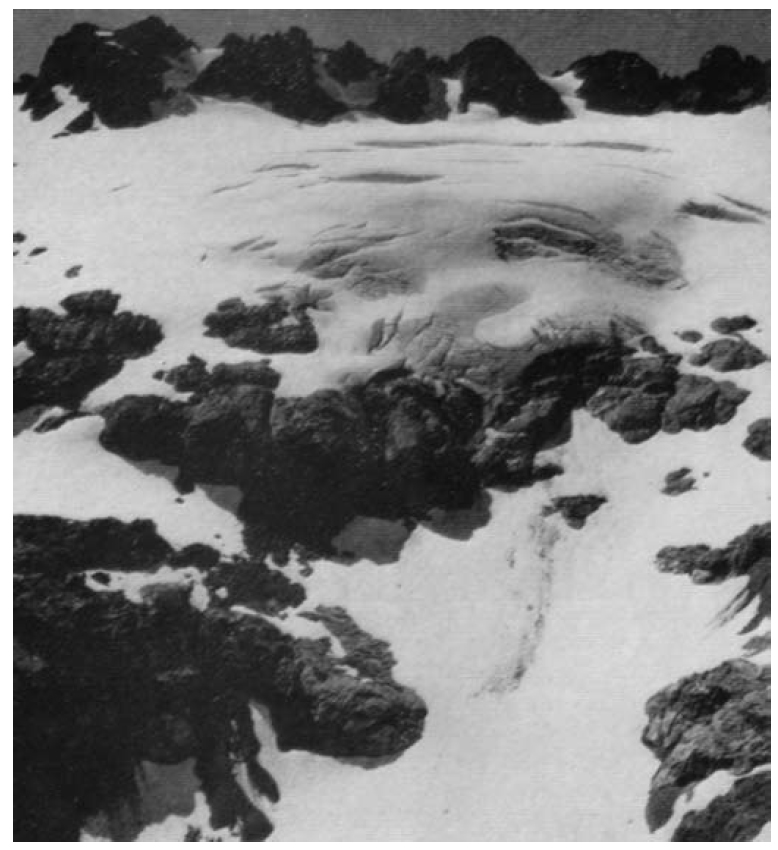

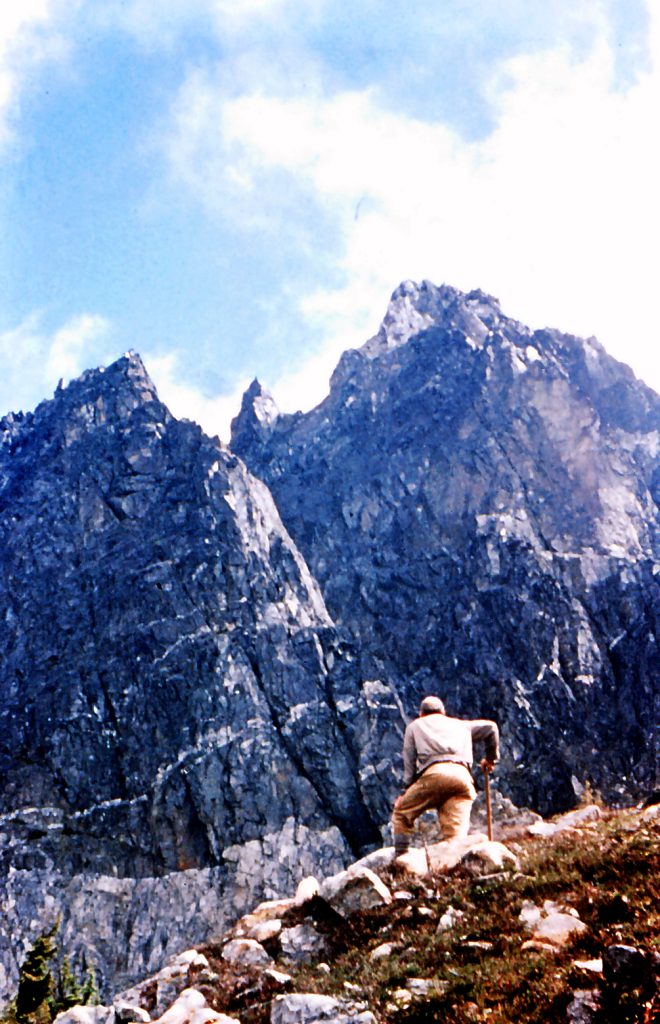

Nine Peaks – Connie Bonner photo.

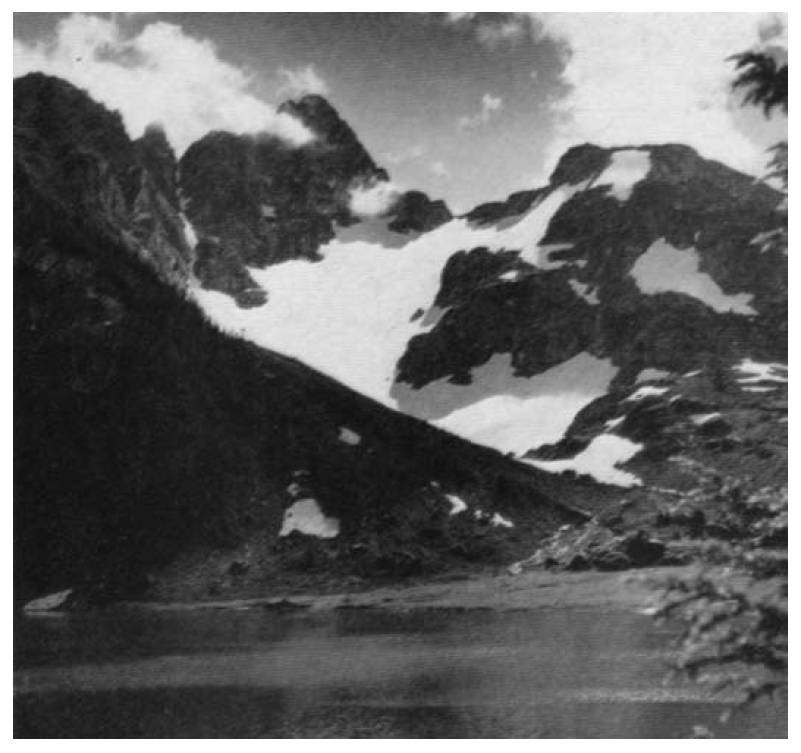

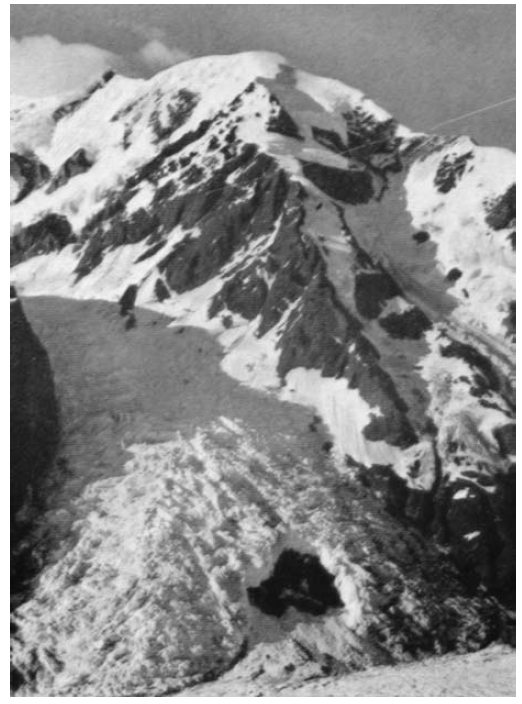

Cream Lake and Mt. Septimus – Connie Bonner photo.

1955 Cream Lake Route Map

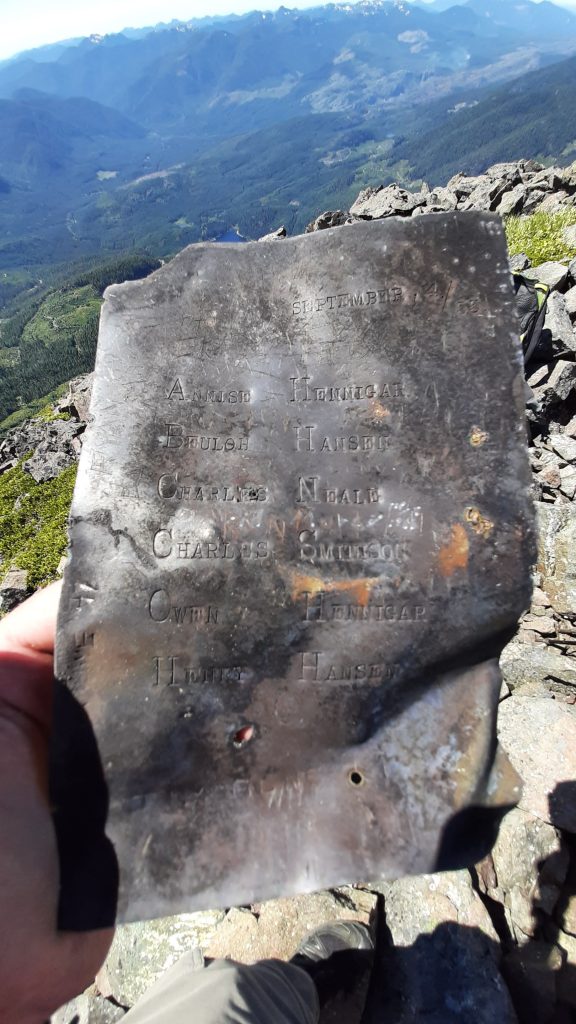

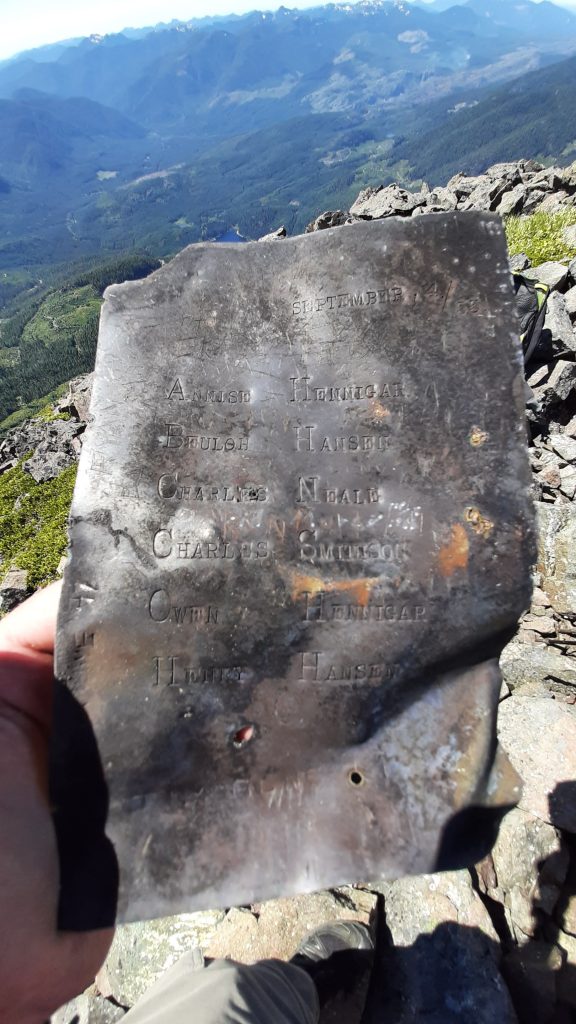

Pinder Peak 4 September 1955

The engraved metal plate with the names Annise and Owen Hennigar, Beulah Hansen, Henry Hansen, Charles Neale and Charles Smithson, that was left on the summit of Pinder Peak in 1955 – Jason Hare photo 2017.

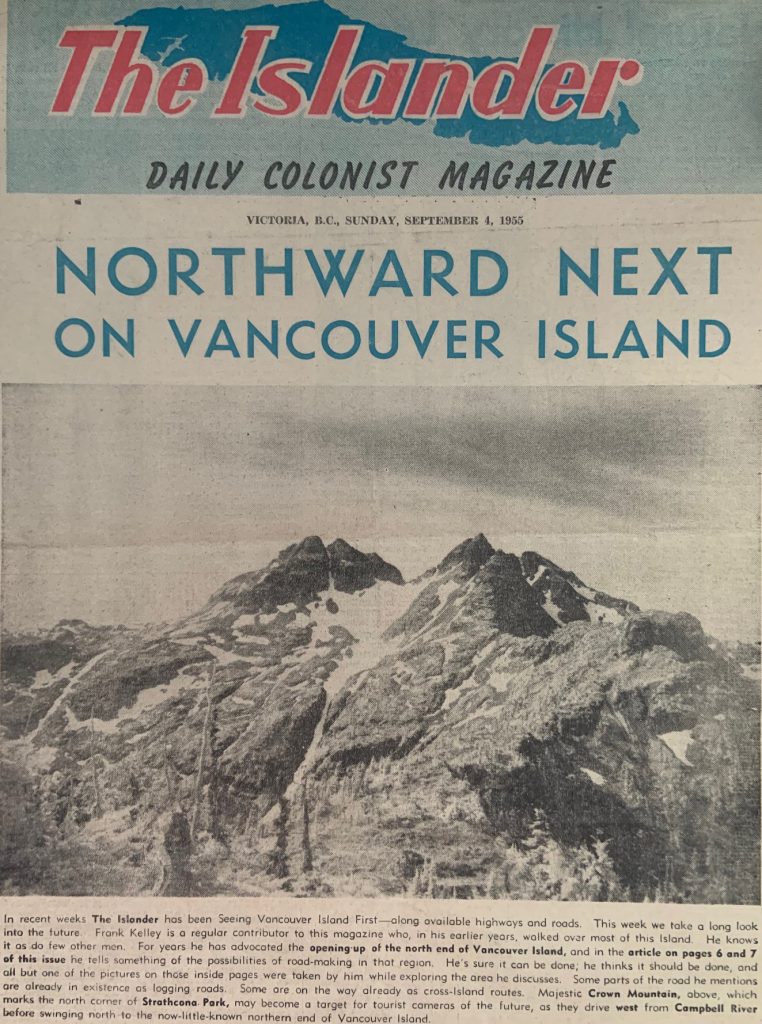

Northward Next on Vancouver Island

Reported in The Daily Colonist (The Islander Section) Sunday September 4, 1955. p.1.

Northward Next on Vancouver Island. In recent weeks The Islander has been Seeing Vancouver Island First — along available highways and roads. This week we take a long look into the future. Frank Kelley is a regular contributor to this magazine who, in his earlier years, walked over most of this Island. He knows it as do few other men. For years he has advocated the opening-up of the north end of Vancouver Island, and in the article on pages 6 and 7 of this issue he tells something of the possibilities of road-making in that region. He’s sure it can be done; he thinks it should be done, and all but one of the pictures on those inside pages were taken by him while exploring the area he discusses. Some parts of the road he mentions are already in existence as logging roads. Some are on the way already as cross-Island routes. Majestic Crown Mountain, above, which marks the north corner of Strathcona Park, may become a target for tourist cameras of the future, as they drive west from Campbell River before swinging north to the now-little-known northern end of Vancouver Island.

Nine Peaks

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Tuesday November 8, 1955. p.12.

BEAUTY SPOT in southern portion of Sathcona Park is Cream Lake, left by glacier that has receded back to Mt. Septimus in last century. Green, crystal-clear lake is part of Buttle Lake watershed, but Nine Peaks Mountain is in watershed of Great Central Lake. Spectacular jagged peal is five miles due south of Cream Lake. (Photo by Connie Bonner, Cobble Hill.)

Big Interior Mountain

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Wednesday November 16, 1955. p.6.

ONE OF MANY majestic peaks in Strathcona Park is Mount Big Interior, 6,107 feet, that rises above Della lake. Prospector diggings, mainly for copper, can be found high on slopes of Big Interior. Della lake is source of famous Della falls that tumble 1,600 feet to form Drinkwater creek, which in turn flows eight miles to Great Central lake. (Photo by Connie Bonner.)

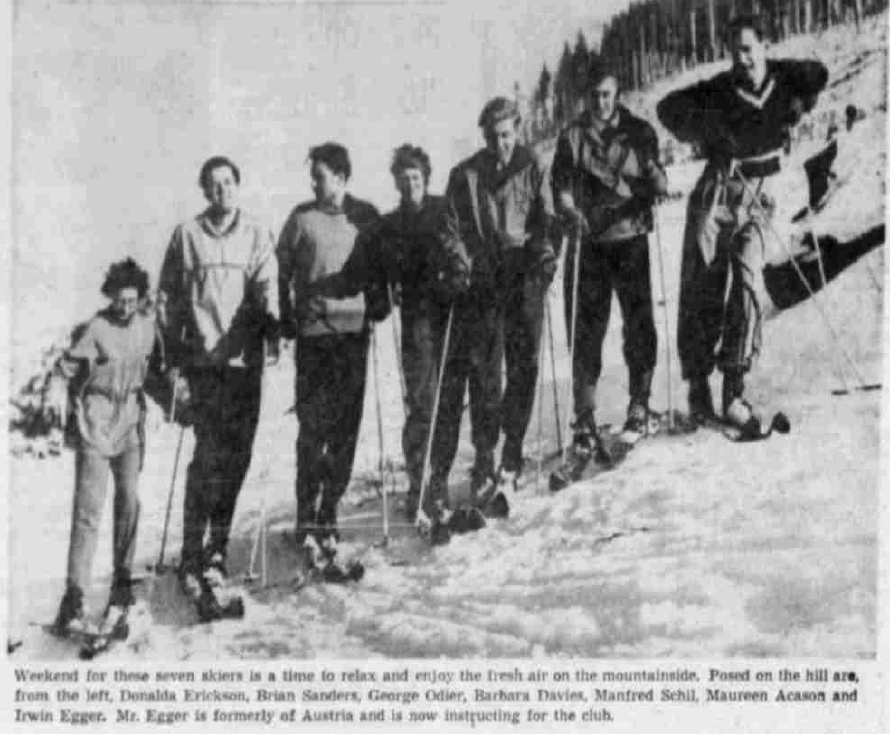

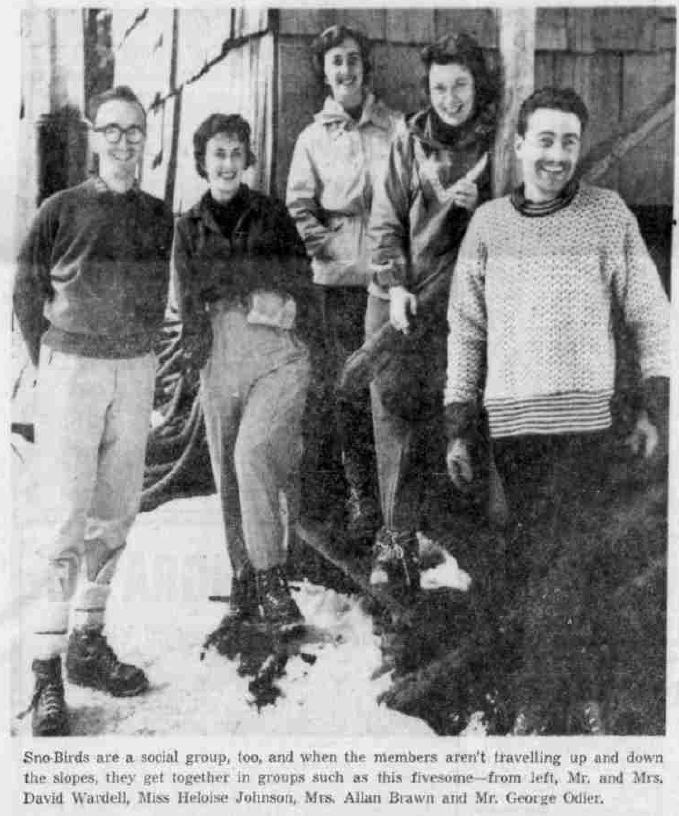

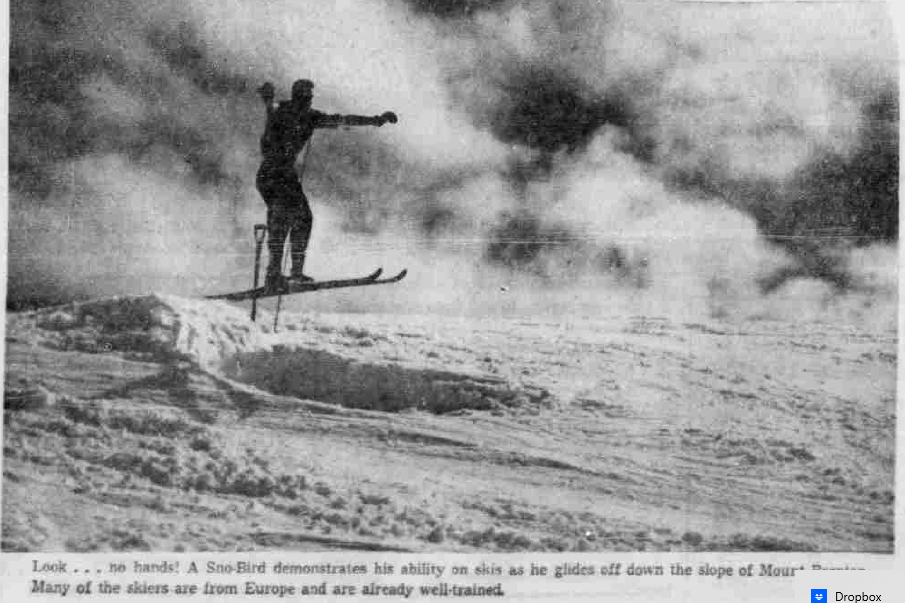

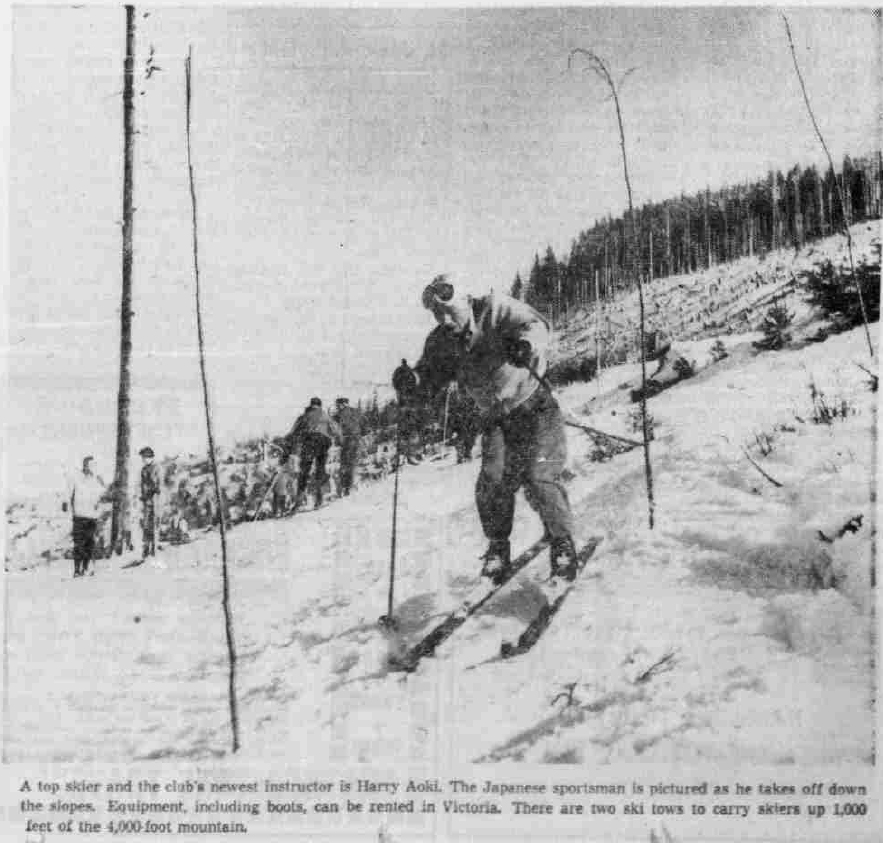

A Sno-Bird Takes Flight

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Thursday December 8, 1955. p.10.

A Sno-Bird Takes Flight

The people you see with their eyes on the skies are not air raid wardens; they are members of the Victoria Sno-Birds Ski Club, scanning the heavens for the welcome sight of snow clouds. The Sno-Birds are having a thoroughly enjoyable season at Mt. Brenton Ski Camp and seek new members. Among the most skillful in the club is graceful Frank Jensen, former professional at Forbidden Plateau.

1956

ACCVI executive:

Chairman – Bill Lash

Secretary – Margery Thomas

Events:

The first official outing of 1956 was a boat trip to Mt. Tuam, Salt Spring Island.

Six Section members attended the ACC Columbia Icefields Ski Camp.

March – The sections annual banquet was held at the Pacific Club. The guest speaker was Fred Ayres of Portland. He showed slides and told the story of his climbs in the Andes.

Several ski trips to Mt. Baker, usually in small parties of two or four members. A ski camping trip to Mt. Porter near Port Alberni was carried out by two members but they were soon chased home by a downpour.

June 10 – Four members hiked up Mt. Sutton near Lake Cowichan. Summit weather was misty with snow flurries but a pleasant boil-up was organized.

July 1 – A club trip to the Dosewallips in Washington with an attempt by fifteen members, the second year in a row, to climb Mt. Constance. This mountain has been eluding the section for several years mostly because of the foul weather it brews. Five climbers had an easy scramble to the summit in glorious weather, despite tales of icy slopes and finger traverses.

July 7 – Three members climbed Hkusam Mountain at the extreme northern end of the highway on the east coast of Vancouver Island. The day was clear and the view of Johnstone Straits and the Coast range was magnificent.

August 25 to September 2 – Nine members attended the section camp at Garibaldi. They were all flown into Garibaldi Lake where they had the area to themselves. The climbers bagged Black Tusk, Castle Towers and Mt. Garibaldi while the botanists and photographers explored the meadows, lakes and glaciers. The notorious Garibaldi weather was reasonably kind and the camp was a complete success. A change from the bushwhacking involved on the usual camps in Strathcona Park. Party included: Patrick Guilbride, Syd Watts, ??

November 23/24/25 – Thanksgiving Weekend camping by the Chemainus River. El Capitan Mountain and Mt. Landalt climbed. [Mt. Landalt was changed on 6 May 1975 to Mt. Landale to reflect the correct form of the family name of John James Landale, engineer with the Robert Brown 1864 Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition.]

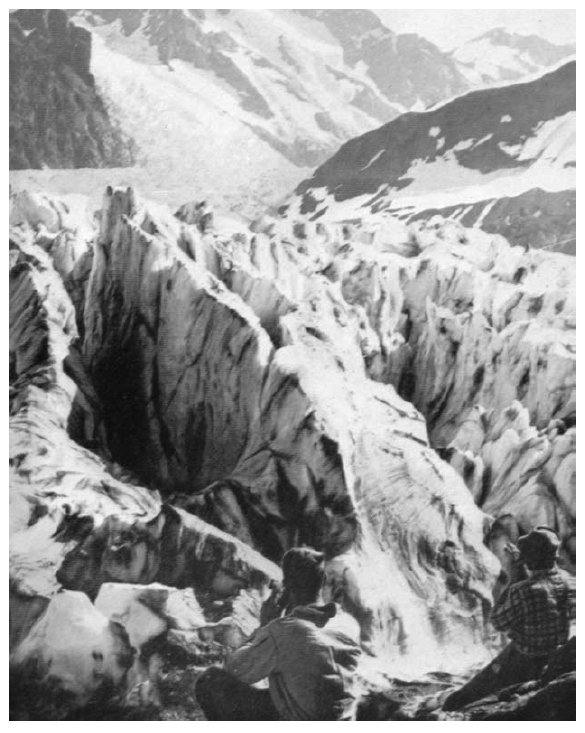

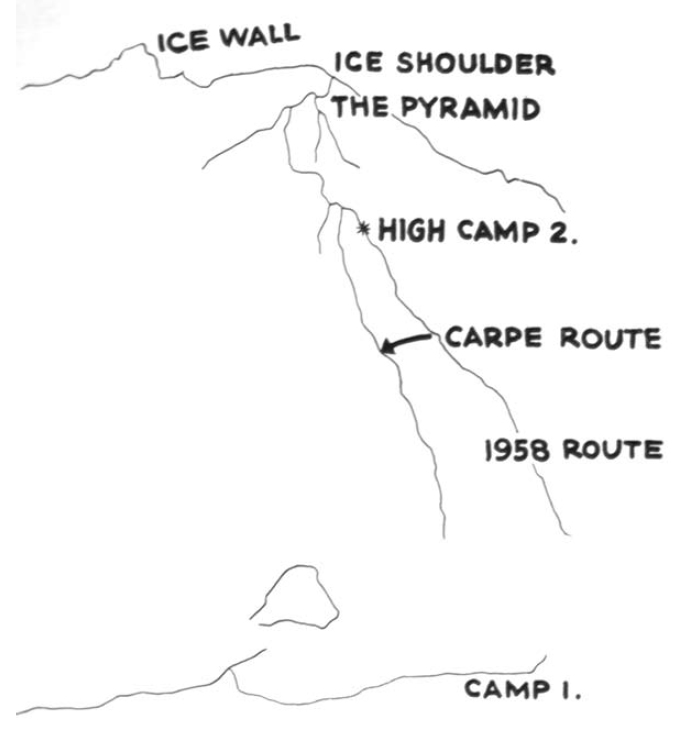

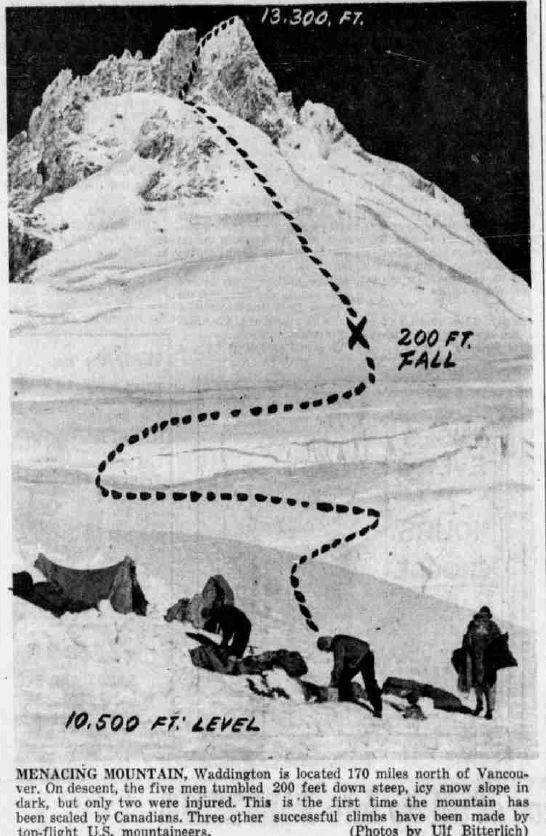

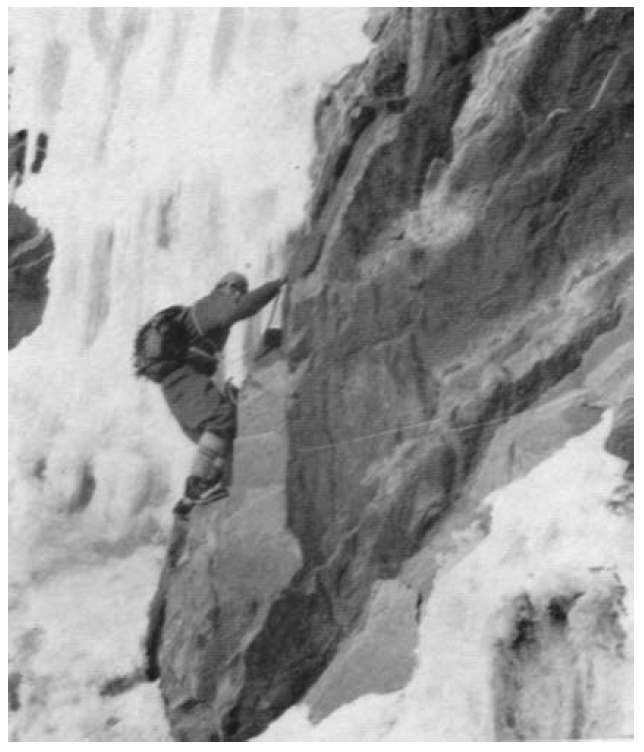

A party of six including two women made the ascent of the Northwest Peak of Mt. Waddington on August 13. Ulf and Adolf Bitterlich, Sylvia Lash, Philippe Delasalle, Sarka Spinkova and Earl Whipple. Three of the party were from the Vancouver Island Section.

November – The annual business meeting of the section was held at the home of Mark Mitchell. Noel Lax was elected Chairman. Ulf Bitterlich showed slides of his ascent of the Northwest Peak of Mt. Waddington.

Noel Frank Lax age 24.

Section members who attended the ACC general summer Glacier Camp in the Selkirks July 16 to July 29: Geoffrey Capes, Aileen Aylard, Muriel Aylard, Adolf Bitterlich, Rex Gibson, Ethne Gibson, William Innes, Sylvia Lash, Bill Lash, Eleanora “Nora” Piggott.

Section members who passed away in 1956: Cyril Jones, Alan Morkill, Leroy Cokely, Albert MacCarthy

Funeral Rites Thursday for Cyril Jones

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Wednesday January 25, 1956. p.17.

Cyril Jones, Victoria’s former city engineer and a well-known alpine climber, died at the Royal Jubilee Hospital Tuesday. He was 66 years old. Mr. Jones entered hospital four days ago. He had been in poor health since he underwent a brain operation in Vancouver last August. He was city engineer from 1949 until his retirement at the end of 1955. Born in Swansea, Wales, and a resident of Victoria for the past 31 years, Mr. Jones was a veteran of the First World War. He served with the Royal Engineers and was wounded in Flanders. For a time Mr. Jones was a science master at Brentwood College and a surveyor. An active outdoor man, Mr. Jones was a member of the Alpine Club of Canada. He had climbed some of the highest peaks on Vancouver Island, as well as in the Rockies. He is survived by his widow; a son, Peter, in Vancouver; a daughter, Mrs. Pamela Stone, Nanaimo, and another daughter in England.

Mt. Brenton Ski Rivalry Resumes

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Thursday March 1, 1956. p.11.

Traditional skiing foes, Victoria and Courtenay, will resume their rivalry this week-end in the sixth annual Mt. Brenton Trophy. The Victoria Sno Birds will host the visiting team for the annual races at Mt. Brenton. In conjunction with the team trophy event will be an individual competition open to all Canadian Ski Association authorized racers.

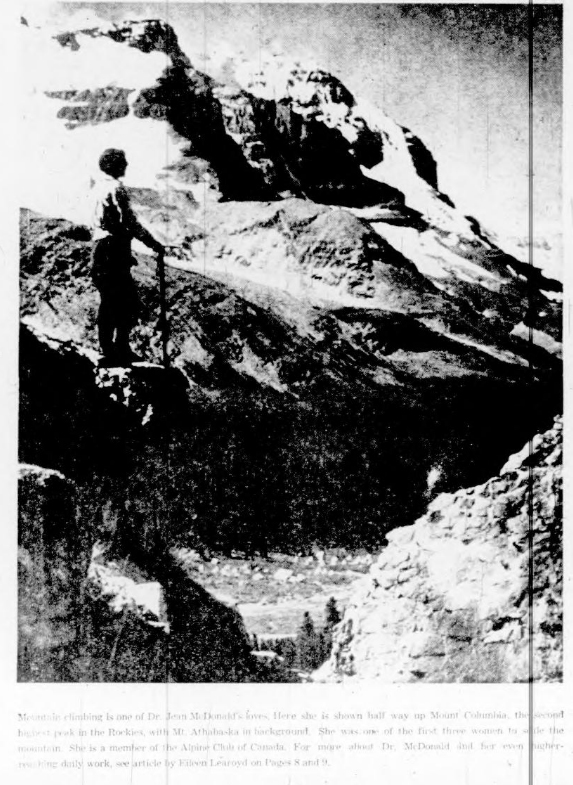

Dr. Jean McDonald

Reported in The Daily Colonist (The Islander section) Sunday April 22, 1956, p1 & 8.

Mountain climbing is one of Dr. Jean McDonald’s loves. Here she is shown half way up Mount Columbia, the second highest peak in the Rockies, with Mt. Athabaska in background. She was one of the first three women to scale the mountain. She is a member of the Alpine Club of Canada. For more about Dr. McDonald and her even higher-reaching daily work, see article by Eileen Learoyd on Pages 8 and 9.

Dr. Jean McDonald looks up from her computations…

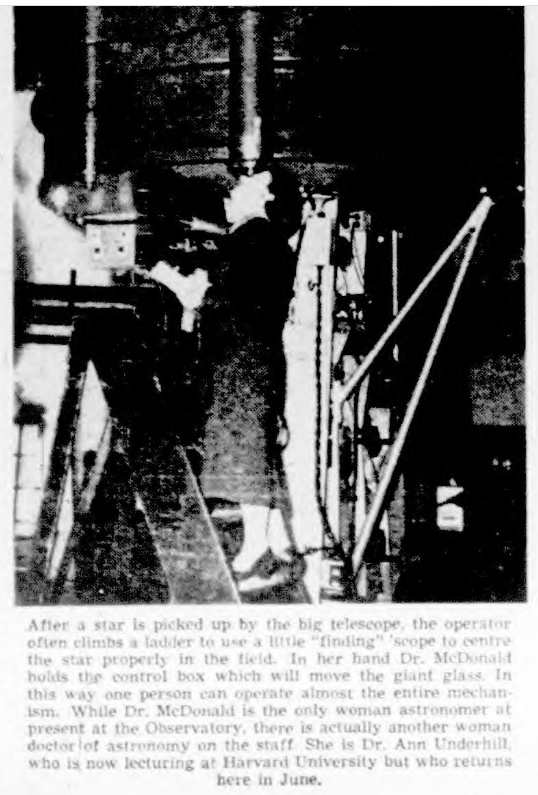

After a star is picked up by the big telescope, the operator often climbs a ladder to use a little “finding” scope to centre the star properly in the field. In her hand Dr. MeDonald holds the control box which will move the giant glass. In this way one person can operate almost the entire mechanIsm. While Dr. MeDonald is the only woman astronomer at present at the Observatory, there is actually another woman

doctor of astronomy on the staff. She is Dr. Ann Underhill, who is now lecturing at Harvard University but who returns here in June.

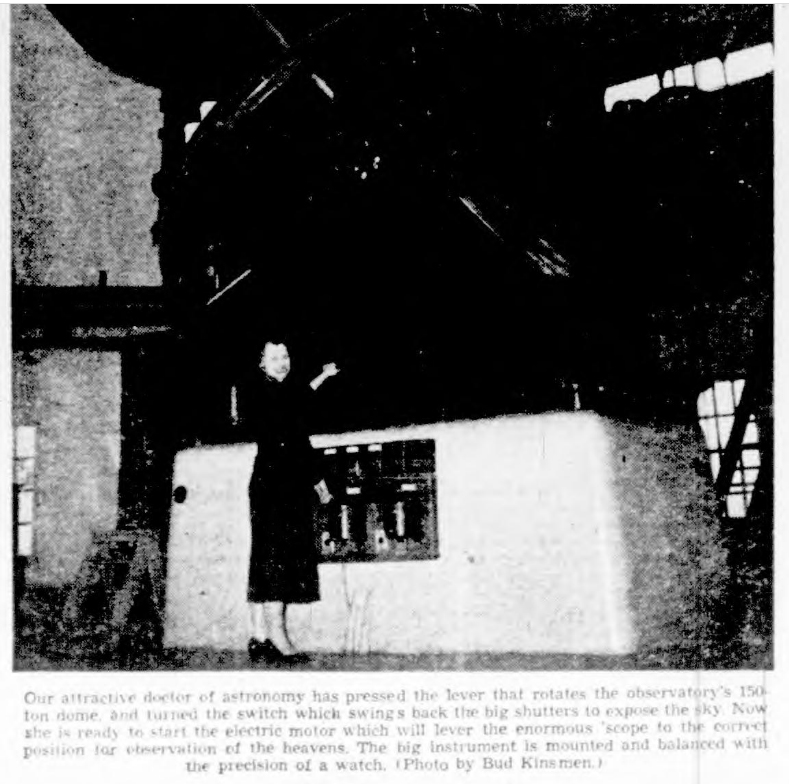

Our attractive doctor of astronomy has pressed the lever that rotates the observatory’s 150-ton dome, and turned the switch which swings back the big shutters to expose the sky. Now she is ready to start the electric motor which will lever the enormous ‘scope to the correct position for observation of the heavens. The big instrument is mounted and balanced with the precision of a watch. (Photo by Bud Kinsmen. )

Resting In a World of White

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Saturday April 7, 1956. p.14.

Relaxing for the moment on the wintry white slopes of Mt. Brenton are skiers Barbara Davies and George O’dier. Skiing is good on Brenton now, with a snow depth of 10 feet and new snow at the top. Melting snow on the lower slopes has shortened the hike to the cabin to three miles. Spring season is under way.

Fine Skiing for All Their Goal

Reported in The Daily Colonist The Islander section Sunday April 8, 1956, p12.

Three European members of the Sno-Birds ski club prepare to show Canadian skiers how to control their skis on the soft, fluffy powder on Mt. Brenton.

Fresh fall of snow outside Son-Birds’ ski cabin on Mt. Brenton. (Photos from the author.)

Soldier, Scholar, Gardener

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Tuesday May 1, 1956. p.4.

Alan Morkill will not see Victoria’s radiant spring time gardens again. He died when the blossoms he so much loved were coming into bloom. But by those who knew how much he had to do with making the city the beauty spot it is, he’ll always be remembered with tenderness and gratitude. Born in Sherbrooke, Quebec, of an old and distinguished family, he came to British Columbia in his teens and entered the Bank of Commerce. Badly wounded, a mere lad, he came home from the First World War a captain with MC and bars. Thought a bank manager when Second World War broke out he enlisted as a private, rose to be a major and second in command at Debert. He married Eleanor Francis Mara, daughter of a well-known Victoria family, a nice of Sir Frank Barnard and Senator Barry Barnard. Mrs. Morkill was for some years commissioner of Girl Guides for British Columbia. Banker, gallant soldier, scholar, very prefect gentleman, Alan Morkill was loved by all with whom he came into contact; helpful without a stint to those in trouble. But he will probably be most remembered as a collector of plants, a gardener. He explored the mountains of British Columbia far afield; brought home specimens to acclimatize and propagate. He fired numbers of people with his own enthusiasm; started the Rock Garden Club and was for many years its president and mainstay. Spring Garden’s Week would never have become the international festival it is without Alan Morkill’s help. A modest man he’ll be remembered in the modest flowers that bloom in Victoria’s rockeries. – Gordon Cameron.

Mount Arrowsmith Chalet Dedicated

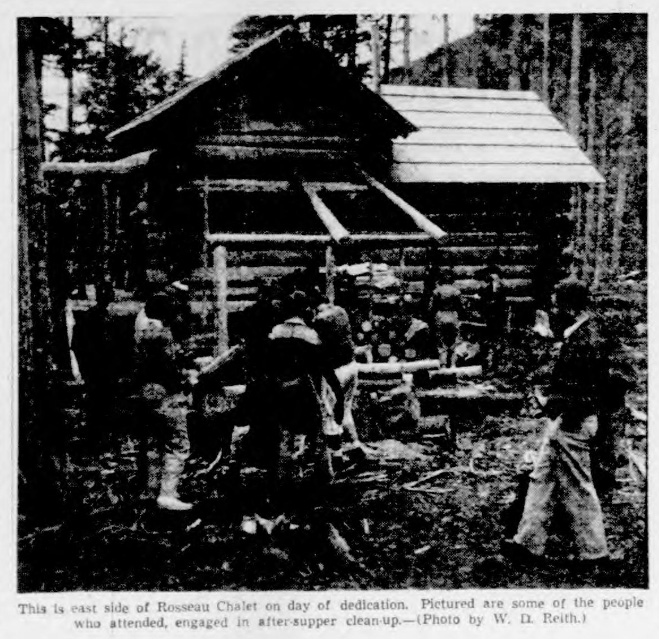

Reported in the Twin City Times Thursday July 5, 1956. p.1.

A chalet, at the 3500-foot level on Mount Arrowsmith was officially dedicated to the use of youth organizations of the Alberni’s in the memory of the late Ralph Rosseau when ceremonies were held Saturday afternoon. The cabin started by Mr. Rosseau and completed by volunteers, was declared officially open by Mrs. Rosseau who cut the yellow cedar bark ribbon across the doorway. Bill Reith, prominent in the Boy Scout movement here, unveiled the cedar and brass plaque on the hostel. The plaque was the work of Carl Rogg and Wally McEachern. Also taking part in the ceremonies was Art Skipsey, who told how the project was undertaken by volunteers after the death of Mr. Rosseau in a mountain accident two years ago. Approximately 85 persons attended, many of them remaining the night and taking part in a climb to the summit of the mountain. Following the dedication ceremonies, guests signed their names in a guest book made for the hostel by Pete Karsholt. An outdoor supper was served and Scouts and Guides presented entertainment to the group gathered around campfires. Color slides including some taken by Mrs. Rosseau and others showing progress work on the chalet were shown. Mr. Art Skipsey, Hayo Huisman and George McGarrigle received humorous awards for their part in the project.

Rosseau Chalet Officially Open; Dedicated to Youth

Completed Chalet Stands as a Perpetual Memorial to Ralph Rosseau and His Love for The Mountains: Two Years to Finish

Reported in the West Coast Advocate Thursday July 5, 1956. p.7.

Saturday, June 30, 1956, was a happy day for Alberni Valley Mountaineers. Rosseau Chalet, 3,500 feet up on the western slopes of Mt. Arrowsmith, was officially opened and dedicated to the use of young people and others interested in mountain climbing and skiing. Two years earlier, almost to the hour, a snow bridge on Mt. Septimus collapsed, dropping Ralph Rosseau to his death. Ralph was well known and much liked by people of the Albernis, a quiet man with a ready smile and a willingness to help others. He loved mountains, rarely missed an opportunity to climb or ski and almost every trip added to his collection of beautiful colour slides. The origin of the Rosseau Chalet came as a direct result of closing China Creek watershed to the public about eight years ago. Until then, Mr. Rosseau and other skiers had used King Solomon Basin, headwaters of China creek, as a winter playground. Several exploratory jaunts on Arrowsmith finally revealed an ideal ski run and near it a cabin site. Ralph and Lillah, his wife, liked the area so well that following the construction of their small, log ski hut they decided to build a big cabin which would give an extra measure of comfort during their trips – and more room for friends. At the time of Ralph’s death, the cabin was better than half completed. Mrs. Rosseau felt that it would have been her husband’s wish to have it completed for the use of young people, many of whom he had given their first taste of mountain air. A committee, headed by Art Skipsey, was set up to carry out the job of completing the cabin – a task which took nearly two years and a great deal of hard work, as every ounce of material not indigenous to the immediate area had to be packed in on men’s backs. It could not have been a better day for the opening. Rain clouds of earlier in the week moved aside for a clear, bright day, just pleasantly warm and affording a good view of the valley below. Camera enthusiasts were able to make good use of their film. Over eighty people, including Guides and Scouts, attended the opening. A few went up on Friday to help with last-minute preparations, the majority arrived from early Saturday until a few minutes before the opening ceremony. The trail, in distinct contrast to the earlier days of the cabin, is now clearly marked and well-trodden. The most outstanding improvement is a new, amply wide suspension bridge which replaces the somewhat precarious hemlock log across the rushing water of the Cameron River. This fine bridge is due to the efforts of George McGarrigle. At 4 p.m. Art Skipsey began the opening ceremony by giving a short resume of the cabin’s history, then presented Mrs. Rosseau with the key. At the time she was also presented with a pretty corsage of mountain flowers. Mrs. Rosseau cut the ribbon of yellow cedar bark stretched across the doorway and declared the chalet open. Inside on the west wall is the joint work of Wally McEachern and Charlie Rogg – a brass memorial plaque, mounted on a yellow cedar shield inlaid with red cedar. Above the plaque is a portrait of Ralph Rosseau, flanked by a photograph of Mt. Septimus, one peak named after Rosseau. Placed nearby is a beautiful visitors’ book, made by Peter Karsholt. The covers are yellow cedar burl cut to show a marking similar to birds-eye maple. The first pages are suitable illustrated with pen drawings in mountaineering motif done by Mrs. Jennie Reith. Before and during the short dedication talk and prayer the plaque was concealed by a curtain of red cedar bark cleverly fabricated by Mrs. Dorothy Armstrong. Mountain heather and purple penstemon tastefully decorated the valance of the bark curtain which was drawn aside to conclude the dedication. The ceremony was closely followed by an excellent supper prepared and served by the Rangers (senior Girl Guides) under the direction of Mrs. Abernethy and Mrs. Armstrong. After supper those who were staying the night, with the intention of climbing Arrowsmith peak next day, went in search of bed places. These varied from bunks in the chalet and neighboring cabins to under the stars on mossy ground beneath a sheltering tree. The evening program of entertainment began with showing a few of Ralph Rosseau’s color slides, views of and from Arrowsmith, early progress of the cabin and two excellent close-ups of ptarmigan. Explanatory comments on the slides were made by Mrs. Rosseau. Also shown were slides by Art Skipsey showing later progress of the cabin building and snow conditions there during last winter. Three comic awards were made in lighter vein to George McGarrigle, Hayo Huisman and Art Skipsey for bridgework.

The construction of the Rosseau Chalet. All photos are courtesy of Louise Eck (nee Rosseau.)

Art Skipsey handing the key to Lillah Rosseau at the opening of the Rosseau Chalet.

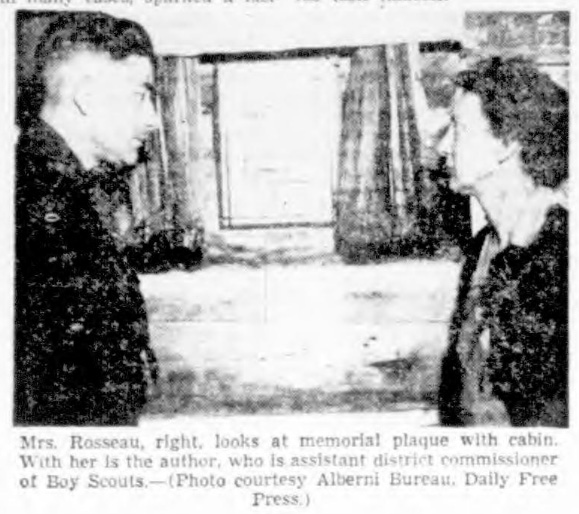

Chalet Honors Mountaineer

Reported in The Daily Colonist (Sunday Magazine) Sunday August 26, 1956. p.12.

By William D. Reith

I remember Ralph Rosseau as a smallish man not much over five feet, energetic, with a ready smile and a willingness to help others. He usually wore heavy walking shoes and walked to and from work to keep him trim for mountain climbing. His slight stoop was grinningly attributed to packboard carrying. A stock of somewhat unruly, wavy, brown hair tumbled over his forehead above lovely blue eyes that twinkled humorously unless the situation was very grave indeed. His good humor polarized him with students and parents alike during his many years as teacher in Alberni Valley schools. From 1950 until his death, he was principal of Gill Elementary School. Ralph was killed two years ago while climbing Mount Septimus with his wife Lillah and two friends. His companions, by some miracle, escaped sharing his fate when a snow bridge they were crossing collapsed, dropping him to rocks below. Since then, a peak nearby the accident scene has been named Mount Rosseau in his honor.

Cabin Dedicated

On June 30 this year more than 80 of Ralph Rosseau’s friends, many of them Scouts and Guides who had hiked or climbed with him in the past, climbed 3,500 feet up the western slopes of Mount Arrowsmith to dedicate a log cabin as his memorial. Ralph had a great love for mountains and rarely missed a chance to climb or ski. Once, while yarning, he told me that while teaching in Bamfield, where the only handy hill of any height is the low mound of Pachena Cone [named in 1861 by Captain George H. Richards R.N. 672 m. Pachena in its original form means ‘sea foam’ or ‘foam on the rocks.’] he reckoned he had worn a groove in its side climbing it so frequently, trying to satisfy his appetite for climbing. A keen photographer, he had a wonderful collection of color slides. One I remember particularly was taken from the depths of a crevasse, into which he lowered himself to capture on film the beautiful blue of sunlight filtering through ice. Before his marriage to Lillah he quite often went out by himself, and it was on one of these lone tris across Comox Glacier that he took this unusual crevasse picture. He did not lack courage. Rosseau Chalet came into being as a direct result of closing China Creek watershed to the public about eight years ago. It is now a game reserve and supplies water for Port Alberni. Until it was closed off, King Solomon Basin, headwaters of China Creek, had been a popular ski ground for Ralph and others of similar interests. Left with nowhere handy to ski, he turned to Mount Arrowsmith, outstanding landmark of Alberni Valley’s east wall. A number of exploratory jaunts on Arrowsmith finally disclosed an ideal ski run and near it a cabin site. He and Lillah liked it so well that, on completion of their small log ski hut, they decided to built a big, durable cabin to afford greater comfort during their frequent trips up the mountain—and make room for friends. Ralph had never built a large log cabin before, although he had, as many do, dreamed of having one someday.

Long Study

To make up for lack of experience he gathered all the written information available; studied long and hard, asked many questions—and finally felt prepared to tackle the job. A better site could not have been chosen. Only a few yards from their ski hut, a year-round creek ran by and a view of Alberni Valley unfolded below. Their ski run was only a few minutes away and the summit, to which Ralph had climbed 30 times could be reached in an hour and a half. Building went slowly, trees for logs were carefully selected, peeled and seasoned. Each log consumed about eight hours of work to become part of the cabin. Cedar for shakes was not available nearby—they were split and packed up from half a mile away and 600 feet lower in altitude. Now and then climbers would drop in, wondering about the route to complete the ascent. Often as not, Ralph would drop his work on the cabin to show the way personally. These incidents held up progress, but he did not mind, the job was meant to be pleasure, not a burden. That he took pride in careful workmanship is evident to those seeing the well-fitted sturdiness of the cabin today. At the time of his death the cabin was more than half completed. Mrs. Rosseau felt that it would have been her husband’s wish to complete it and make it available to young people interested in climbing and outdoor recreation. Often he had taken parties of students, Scouts, Guides and young people of other organizations on mountain climbs, giving them an introduction which, in many cases, sparked a lasting interest. No one could miss his love of mountain environment or fail to be influenced by it. Many times I’ve heard, “Never forget my first trip Mr. Rosseau took us—he was wonderful.”

Two Years

A committee headed by Arthur [Art] Skipsey, a keen Alberni Scoutmaster, was set up to administer the work of completing the cabin. The job was done in two years of weekends and other spare time by people too numerous to list. They worked hard and worked well. Trips were made up the mountain in weather that would otherwise have kept them at home, and loads were carried that would not have been carried for any lesser reason. A fine suspension bridge was built across the Cameron River to replace a log previously used, the trail was relocated in places and improved throughout.

Ceremony Short

As opening day approached, many speculations were made regarding weather which had been wet and dreary throughout June, but nature smiled and the weather was perfect. Even those unaccustomed to the strenuous climb enjoyed themselves on the trail. Songbirds cheered them on and whiskey-jacks came to beg whenever food was produced. The ceremony was short but impressive. A brief talk on the history of the cabin preceded Mrs. Rosseau declaring the Chalet officially open by cutting an appropriate ribbon of yellow cedar bark. Inside a brass plaque was unveiled and the building was blessed to its worthy cause.

Portrait On Wall

On the wall above the plaque is a portrait of Ralph Rosseau, and beside it a large photograph showing Mt. Septimus and Mt. Rosseau. Nearby is a beautiful visitors book—the covers are made of yellow cedar burl—signed by all who attended, and it is hoped will in time fill with names of many who find pleasure in using the cabin. A supper, made by Alberni Valley Guides, followed the ceremony, and the remainder of the evening was spent enjoying campfire singing and skits put on by various groups. Looking down from the Chalet, lakes and waterways shone silvery in fading daylight, city lights twinkled through as darkness welled up to engulf mountains reaching to a clear starry sky. Cabin windows glowed warmly into the night and happy sounds came from within. Everyone was, as it would have been had Ralph completed his task himself.

This is east side of Rosseau Chalet on day of dedication. Pictured are some of the people who attended, engaged in after-supper clean-up.—(Photo by W. D. Reith.)

Scoutmaster Arthur Skipsey, who organized completion of cabin, here with Mrs. Lillian Rosseau Just before cutting “ribbon” of yellow cedar bark. — (Photo courtesy Alberni Bureau, Dally Free Press.)

Mrs. Rosseau, right, looks at memorial plaque with cabin. With her Is the author, who is assistant district commissioner of Boy Scouts.— (Photo courtesy Alberni Bureau, Daily Free Press.)

Mount Karmutzen and Pinder Peak

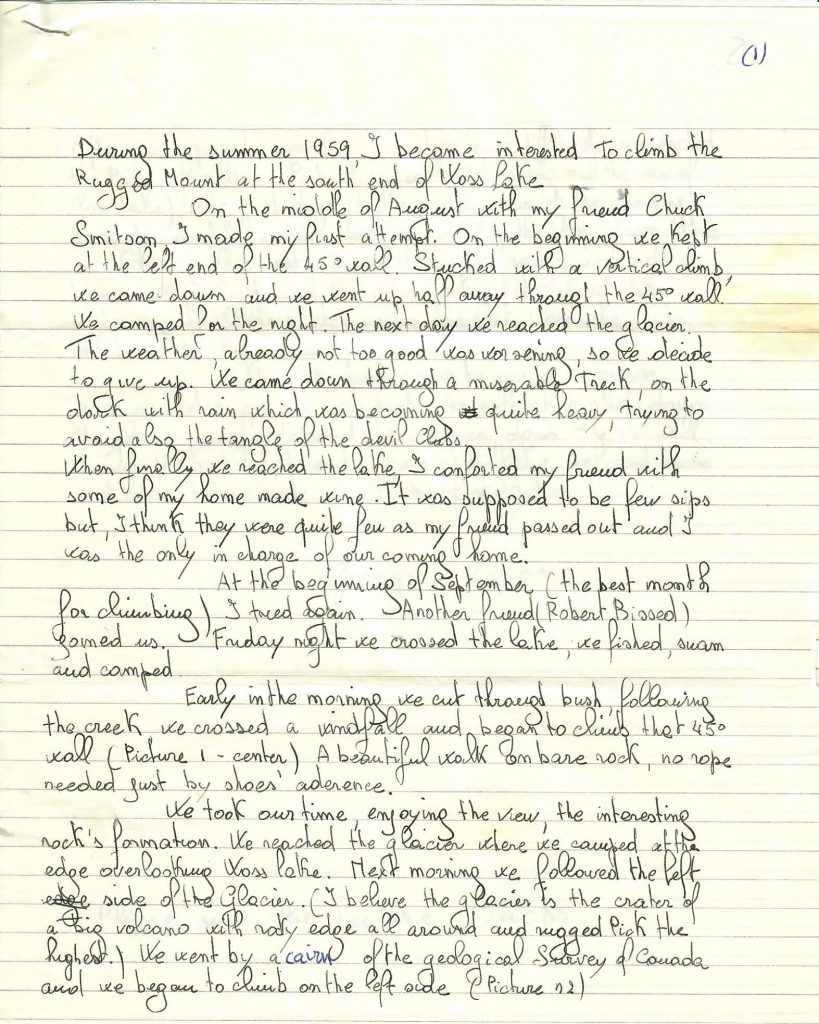

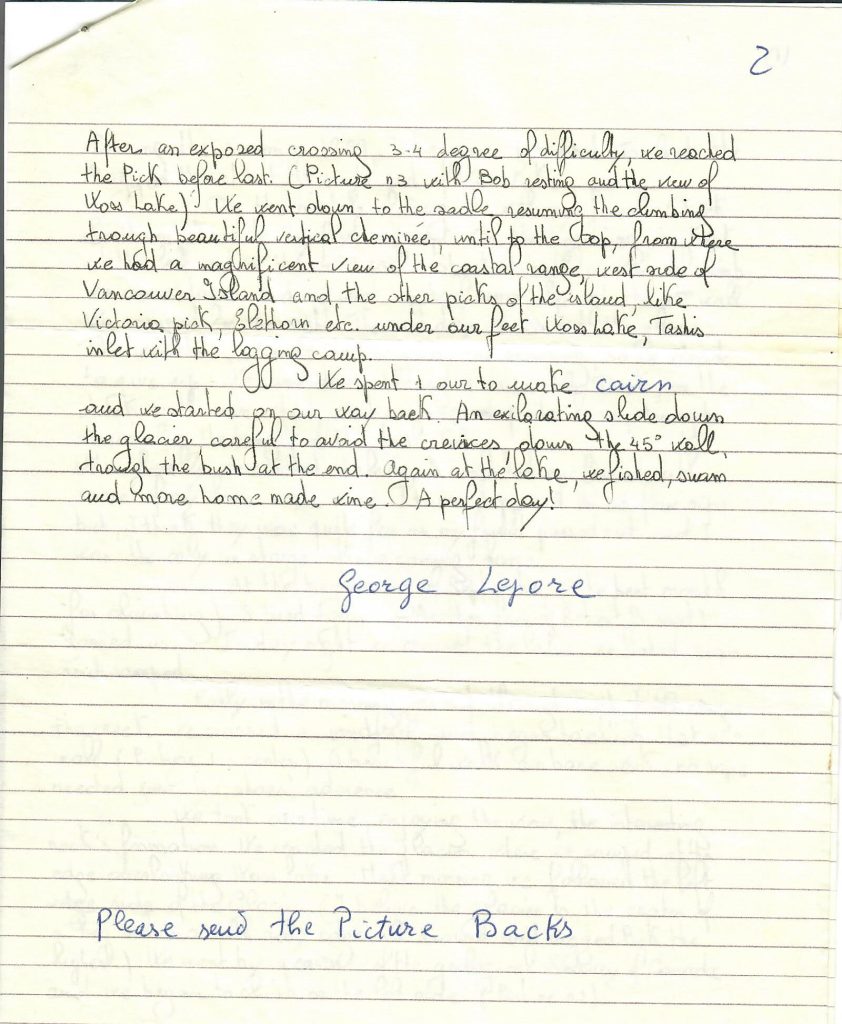

From an interview with George Lepore by Lindsay Elms in the 1990’s.

In 1955, George Lepore emigrated to Canada from Padua, Italy and moved to the Nimpkish Valley. It was while living in Italy that Lepore found a passion for mountaineering and found himself climbing on the steep limestone cliffs of the Dolomites. After moving to the logging village of Nimpkish he reacquainted his interest in mountaineering and started climbing the local mountains, although he found their geology very different to what he was used to. In August or September 1956, Lepore made a long day ascent of Mount Karmutzen with four Italian friends. After rowing from his home across Nimpkish Lake early in the morning, they climbed a steep treed route directly to the summit. Lepore said there was no cairn on the summit so they built one. Not long after climbing Mount Karmutzen he made an ascent of Pinder Peak with another four friends. From the bridge that crosses Atluck Creek on the logging road between Mukwilla Lake and Atluck Lake, they walked down the valley to Atluck Lake and there found a row boat that had been stashed by a friend. Lepore, being the only boatman, rowed them down the lake to a small island. From the island they rowed across to the south shore and began the climb. Big open timber made travelling easy and they arrived on the summit about 1:30 p.m. On the summit they found a large cairn probably built by surveyors in the 1930’s. Lepore normally liked to relax on the summit and spent some time enjoying the view, but his friends wanted to get down and back to Nimpkish for a show that evening. Lepore was rather annoyed so took off running and arrived at the lake shore a couple of hours later. While waiting he fell asleep and woke up at 7:00 p.m. when they finally arrived down. They missed the show!

Mount Karmutzen from the summit of Mount Hoy 2014 – Lindsay Elms photo.

Postscript:

By Lindsay Elms

Mount Karmutzen was adopted 31 March 1924 from the 18th Report of the Geographic Board of Canada. It was identified in Dawson’s geological survey of Northern Vancouver Island (GSC Annual Report, 1886) and labelled on the accompanying map, published in 1887. Karmutzen is recorded as being an anglicization of a local indigenous word of the people living on what is known as Cormorant Island and means “waterfall.”

Lindsay Elms on the summit of Mt. Karmutzen 1997 – Sandy Briggs photo.

Curtis Lyon and Lindsay Elms on the summit of Mt. Karmutzen 1997 – Sandy Briggs photo.

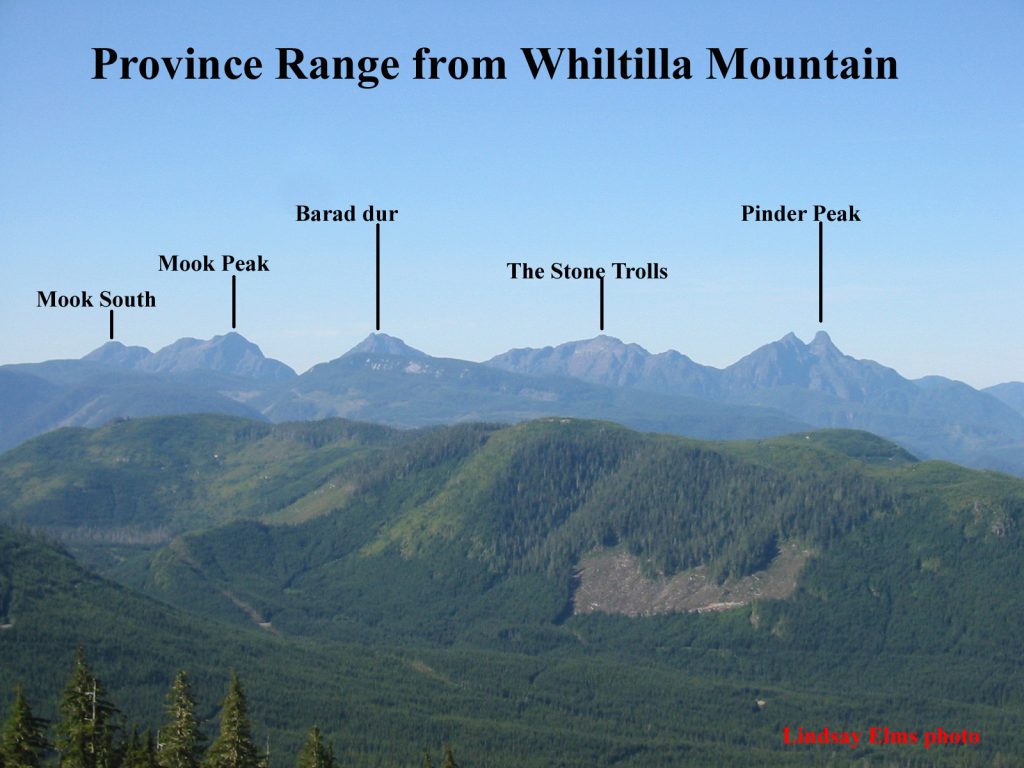

Province Range

In a triangle of land between the Zeballos Forestry Service Road (FSR) and the Artlish Forestry Service Road (FSR) is a range of mountains unofficially called the Province Range which has been known as that for 130 years. Reverend William Washington Bolton named the Province Range after the newspaper of the same name which sponsored The Province Expedition in 1894. He also named the northern most peak Province Mountain but it was officially named Pinder Mountain on 9 January 1934 and then changed to Pinder Peak on 6 April 1950. The first ascent was probably in 1931 when the surveyor Alan J. Campbell (BCLS) set up a survey station at its summit. It was named after William George Pinder (BCLS), an earlier surveyor. The next known ascent was on 4 September 1955 when a party consisting of Annise and Owen Hennigar, Beulah Hansen, Henry Hansen, Charles Smithson and Charles Neale climbed the peak and left a metal plate with their names and date hammered into it.

The engraved metal plate that was left on the summit of Pinder Peak in 1955 – Jason Hare photo 2017.

South of Pinder Peak along the Province Range are three other peaks: The Stone Trolls, Barad–dûr and Mook Peak. Both The Stone Trolls and Barad–dûr were named by Rolf Kellerhals when he and his two children, Heather and Marcus, climbed the peaks in 1981. The name Barad–dûr comes from J.R.R. Tolkiens Lord of the Rings books. Barad–dûr, the Dark Tower or Fortress, was built by Sauron on the Plateau of Gorgoroth in Mordor, not far from the volcano known as Mount Doom. The Stone Trolls were also from a Tolkien book. In The Hobbit each time the trolls settle on a way to cook the dwarves, Gandalf, pretending to be one of them by using a troll voice, starts the argument again. Gandalf stalls and distracts them long enough for the sun to come up, at which point the trolls are turned to stone. The origin of the name Mook Peak is unknown as is its first ascent, but it was likely surveyors in 1931. The name was officially adopted 9 January 1934 as labelled on Alan J. Campbell’s map of the Nimpkish River area. Mook Peak wasn’t climbed very often, but in the 2000’s climbers found an old ten-speed bicycle on the summit.

The infamous ten-speed bicycle on the summit of Mook Peak – Read Guthrie photo.

The south ridge of Mook Peak 2005 – Lindsay Elms photo.

No one knew why it was there or when it was taken up, but in an email from Port McNeill climber and caver Peter Curtis, he told me the story: “Well there was four of us wanting to climb Mook Peak, so we split into two groups and took different routes. The ‘other’ two guys were avid bikers, but also avid drinkers, and they had been drinking before the trip. They decided to go their own route; one carried the wheels while the other took the frame. It was something to do with one of the guy’s young nephews who was mentally challenged and wanted to ride a bike in the mountains … so they planned to tell him there was a bike up on Mook Peak for him. (Not that he would actually go up there, but he would have something to think about, I guess!) Anyway, they drank their way to the summit, met Stu Crabe and I there, and propped up the bike on an open slab. They were both pissed by then! We all made it down ok, thank God! I think it was in the late 90’s. Both guys had done some mountaineering and had climbed many local peaks. One was from Port Alice and the other from Port McNeill.”

A view of the Province Range from Whiltilla Mountain in the Bonanza Range 2005 – Lindsay Elms photo.

The view from the summit of Pinder Peak looking down on Atluck Lake with Nimpkish Lake in the distance – Chauncey McEachern photo.

Looking up at Pinder Peak and Pinder Horn from the Apollo Main logging road 1999 – Sandy Briggs photo.

John Pratt, Lindsay Elms and John Damasche on the summit of Pinder Peak 1999 – Sandy Briggs photo.

The view of Pinder Peak from Pinder Horn 1999 – Sandy Briggs photo.

Pinder Peak (left) and The Stone Trolls from Barad-dûr 2000 – Sandy Briggs photo.

Barad-dûr from the summit of The Stone Trolls 2000 – Sandy Briggs photo.

The summit of Barad-dûr 2000 – Sandy Briggs photo.

Kaouk Peak (northwest of Zeballos) from the summit of Barad-dûr 2000 – Sandy Briggs photo.

City Women Climbs Mount Waddington

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Thursday September 6, 1956. p.16.

A Victoria woman was a member of an Alpine Club of Canada party which in August, scaled Mount Waddington, a 13,200-foot peak, and the highest in B.C. She is Miss Sylvia Lash, 4078 Cedar Hill, school teacher, and member of a mountain climbing family. Her father, A.W. [Bill] Lash, chief engineer for the B.C. Power Commission, and brother Mallory, are well-known alpinists. The ascent of the mountain is the first successful attempt to scale the peak in 20 years. Mount Waddington, situated about 170 miles northwest of Vancouver above Knight Inlet. Miss Lash said food and equipment were dropped by a plane onto a glacier to assist the party climb the mountain. The party made the ascent from base camp in three days, reaching the top on August 13. The climbers, without sleeping bags, spent the night on an open ridge, before making a final assault on the mountain’s second highest peak, about 50 feet below the main summit, Miss Lash said. She modestly admitted that it was “somewhat cold and not too pleasant a night.” Miss Lash said the party was unable to climb the highest peak of the mountain because a large glacier with crevasses barred the way to the main summit. Two climbers tried an alternate route by attempting to scale the face of the mountain, she said, but had to give up due to the lack of equipment.

Highest Yet

“There was a great deal of ice and snow, and it was quite higher than anything I’ve climbed before,” she said. “On our return journey we left some food and equipment on the mountain.” Other members of the climbing party included Ulf and Adolf Bitterlich, well-known Port Alberni mountaineers; Sarka Spinova, Toronto; Philippe Delasalle, Montreal, and Earl Whipple, Boston. The last ascent was in July 1936, by two Vancouver members of the B.C. Mountaineering Club, Denver L. Gillen and William Dobson.

Big Peak Scaled by City Woman

Reported in The Daily Colonist Thursday September 6, 1956. p.15.

A Victoria woman, who has been mountain climbing for relaxation for seven years, was a member of the Alpine Club of Canada party which last month scaled a 13,200-foot peak of B.C.’s Mount Waddington, the first successful ascent in 20 years. Miss Sylvia Lash, 4078 Cedar Hill Road, modestly admitted last night that it was “an exceptional climb. There was a great deal of ice and snow and it was quite a bit higher than anything I’ve climbed before,” she said. A party of six members of the Alpine Club of Canada made the ascent in three days reaching the top August 13.

Highest In Canada

Mount Waddington, located some 170 miles northwest of Vancouver above Knight Inlet, is the highest peak in Canada outside the Yukon. Its main peak has never been climbed by Canadian, and is said to be one of the most difficult climbs in the world. The peak climbed last month is 60 feet below the main peak. “We camped on an island on Franklin Glacier three days after leaving Knight Inlet, said Miss Lash. “It took us four days to climb up and back to camp.”

Weather Perfect

Weather conditions were prefect for the ascent, she stated. Miss Lash, whose profession is now teaching school, is a member of a mountain-climbing family. Her father A.W. (Bill) Lash and her brother Mallory, are both keen alpinists. Miss Lash was graduated from UBC in 1952 with honors in English. In Miss Lash’s party was Ulf and Adolf Bitterlich, well known Port Alberni mountaineers; Sarka Spinkova; Philippe Delasalle, and Earle Whipple. The last ascent was in July 1936, by two Vancouver members of the B.C. Mountaineering Club, Denver Gillen and William Dobson.

Sylvia Lash

Ulf Bitterlich

1957

ACCVI executive:

Chairman – Noel Lax

Secretary – Margery Thomas

Events:

January – A very successful public showing of members’ colour slides was held at the Arts Centre in Victoria.

February – Two ski-trips to Mt. Baker unfortunately the last was somewhat marred by Margery Thomas suffering a fractured ankle.

April 14 – Warm spring weather brought a good turnout for a rock school on Mt. Tzouhalem.

April 22 – Three members made a ski descent of Green Mountain stating the run down was excellent but far too short.

Hkusam Mountain – was again climbed but the view was partly obscured by clouds. An interesting pitch on the ridge allowed us to brush up on our rock-climbing technique.

June – A scheduled club trip to Mt. Whymper was changed due to the closing of the logging roads because of fire hazard. Mt. DeCosmos was climbed instead in heavy rain and led by Patrick Guilbride.

A rock tower near the summit of Mt. DeCosmos, 1957. Pat Guilbride photo.

July 1 – A party crossed the backbone of Vancouver Island from Buttle Lake to Great Central Lake, some 30 miles by way of Flower Ridge and Mt. Septimus. Weather and visibility were mostly bad, but we did see some new country in our Strathcona Park.

July – Paddy Sherman and three others made a number of 1st ascents in the Duffey Lake area.

August – Franks Stapley, George Frazier and Terry Hanrahan climb Elkhorn Mtn. Possibly 3rd overall ascent.

August 24-September 1 – Six members ventured into the Comox Glacier area for a week-long camp with ascents made of Black Cat Mountain, the Comox Glacier, Argus Mountain, The Red Pillar, Mt. Celeste and Iceberg Peak (Rees Ridge).

October – Thanksgiving Weekend started off in a downpour but relented and gave us two fine days to climb an unnamed peak and Green Mountain for the second time this year.

Section members attended the ACC winter ski camp at Maligne Lake in March: Margery Thomas (still in ankle cast) and five others.

Section members who attended the ACC general summer camp at Moat Lake, Tonquin Valley July 21 to August 3: Geoffrey Capes, Rex Gibson, Ethne Gibson, Tom Hyslop, Mark Mitchell, Edith Maurice, Sylvia Lash, Margery Thomas, Harry Winstone.

Section members who passed away in 1957: Rex Gibson, Jennie (McCulloch) Longstaff, Robert Connell, Reginald Chave.

Mrs. Jennie Longstaff Succumbs At 77: Rites Wednesday

Reported in The Victoria Daily Times Saturday February 2, 1957. p.15.

Mrs. Jennie Longstaff, wife of Major F.V. Longstaff, died at her home, 50 King George Terrace Friday night at the age of 77. Mrs. Longstaff was formerly president of the B.C. Protestant Orphanage and treasurer of the Victoria Order of Nurses. She was also a member of the Alpine Club of Canada which she joined in 1913. Her husband is one of the few holders in Victoria of Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal, which was presented to him after the coronation in 1953. He also holds the King George VI Coronation Medal of 1937. Funeral service for Mrs. Longstaff will be held at the Christ Church Cathedral at 2 p.m. Wednesday.

Island Trio Conquers Mt. Colonel Foster

Snow-lashed Climbers Scale 7,000-Foot Peak

Reported in The Daily Colonist Sunday August 4, 1957. p.30.

By G.E. Mortimore